Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

CORO |

|

|

Reviewer: J.

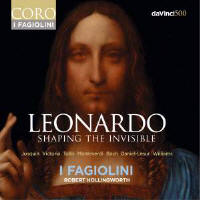

F. Weber The quincentenary of Leonardo da Vinci’s passing has occasioned several recordings focused on his life and influence. This program is not a collection of music by his contemporaries, for only the Agnus Dei from Josquin des Prez’s Missa L’homme armé sexti toni was written in Leonardo’s lifetime. But like other works on the program, his music is a foil to a less familiar sketch of Leonardo, Fantasia dei vinci (or Knot Design, as here). The connection is explained, as it is for each selection, by Martin Kemp on the art and Robert Hollingworth on the music. “Josquin and Leonardo would surely have known each other in Milan,” Hollingworth asserts, accounting for the only “real-life art/music connection on this otherwise fantasy recording.”

Other pairings not so well

connected are titular, as the up-to-the-minute link between Leonardo’s

Salvator Mundi (sold for a record-breaking $450,000,000 less than a year

before the recording was made, only to vanish from sight ever since) and

Thomas Tallis’s anthem from the 1575 collection. It is followed by the

beginning of Herbert Howells’s Requiem, which bears the same title. The

Mona Lisa matches a Monteverdi madrigal, Era l’anima mea, which

tells of “a gaze of such mercy” coming from “those beautiful eyes.” Clever,

if the poem were only printed for easy reference. St. John the Baptist

is less obviously connected with an excerpt from Jean-Yves Daniel-Lesur’s

Le cantique des cantiques. The Last Supper is more clearly

related to a Tenebrae responsory of Victoria and a different one by Edmund

Rubbra. (I’m not sure everyone will appreciate the members of I Fagiolini

posing in a reenactment of the painting.)

Another appropriate connection

is The Musician, Portrait of a Man with a Sheet of Music, the man

being Atalante Migliorotti, a friend of Leonardo’s who played the lira di

braccio (as Leonardo also did). The music is Monteverdi again, Tempro la

cetra, with its string accompaniment of the singer. The Five

Grotesques, from a sketchbook, is matched very neatly by the sound of a

scene from Vecchi’s L’Amfiparnaso. The Vitruvian Man as a study in

proportions fits the first section of Bach’s The Art of Fugue. The

Battle of Anghiari (1440) is only Rubens’s recreation of a lost mural of

Leonardo, but it fits Janequin’s La guerre, which dates from 1528.

The Annunciation is rightly called “a perfect match” for Victoria’s

Alma Redemptoris mater. Head of a Woman with Untidy Hair is less

clearly reflected in the woman who is the source of sweet pain as well as

peace to Petrarch in Cipriano de Rore’s Or che’l ciel e la terra. The

lack of a printed text is ironic, since the music “does not provide an easy

way to hear the text on initial listening. But look at the sonnet itself.”

Not easy to do. The program ends with one of many works of Adrian Williams

commissioned by I Fagiolini, this one dedicated to Leonardo: Shaping the

invisible is the longest work on the program and gives the disc its

title. To get the texts and translations online, each composer’s name on the website must be clicked separately. The 32-page booklet has generous color prints of the subjects with the paired commentaries, but more than in most cases, printed texts should have been more accessible, given their connection with the works reproduced. A lot of thought must have gone into preparing this program, even if some couplings are more apparent than others. Each piece is sung in appropriate style, resulting in much contrast as the program unfolds. Nice try.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|