Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: Arcana |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

There can be no doubt that

once Handel had established himself as the leading opera composer in London,

his competition would begin to import other famed Italian composers as his

rivals. Not only was this a long-standing practice used to enhance

reputations and increase receipts, it also extended to the various main

singers as well. These were rival castrati, whose own abilities were

exploited by Handel and his colleagues in an attempt to outdo each other and

win renown. The feuds were often more congenial than violent, but that

didn’t prevent partisans from being both vocal and sometimes demonstrative

in their support of their favorites. The winners, of course, were the

composers themselves, for the rivalry often meant a string of commissions

that could be extremely lucrative. Moreover, the fact that they were rivals

did not preclude their music from being excerpted or interpolated into each

other’s works as a sort of pastiche. One of these newer (and younger) rivals

was Nicola Porpora, who eventually wound up in Vienna living underneath the

librettist Metastasio and becoming the teacher of Joseph Haydn. Still,

partisanship sometimes spilled over into overt violence. All schemes for dominance aside, the rivalries produced some remarkable music for their intended star singers, and though one might be excused from really wanting to hear it as part of the long (and sometimes tedious) opera serias as a whole, such a collection demonstrates that these pieces could have a life of their own; indeed, if one was a sensation, it was often repeated as many times as necessary on the spot, making the original opera considerably longer than usual. The main singers for these works were probably Farinelli and Senesino, but others such as Caretstini also participated. As a group, it should be noted, finally, that the rivalry was quite the match between the older opera seria style of Handel (still popular in London) and the newer one of Porpora (adding a hint of things to come).

All of the arias are in da

capo format, which means that they should have some sort of musical contrast

in the B section. By the 1730s, however, the B section was more or less

identified only by a thinner texture. The rivalry produced some really

challenging and impressive pieces. For example, the disc opens with the aria

“Sta nell’ircana” from Alcina of 1735, which is a tour de force, with wind

and horn writing and running vocal lines that would have been a challenge

even then. Porpora’s first number, “Nume che reggi” from Arianna a Naxo,

presents a sort of reverse contrast, since it is perhaps more Handelian than

Handel; given that it was one of the first of that composer’s works to be

performed in London, it is not surprising that he eased his way into the

public’s awareness. A couple of years later, when his reputation had been

established, he wrote Calcante e Achille, and the aria “Q questa man” starts

right out of the shoot with some wildly fantastic coloratura. Here we are in

the realm of Farinelli, who was noted for his extreme vocal dexterity. The

foil to this is the aria “Scherza infida,” likewise from Ariodante, with its

soaring and languid line that shows he demanded both ability and emotional

sustaining power, before adding just a touch of coloratura to the B section.

Porpora’s final number is a flowing minuet (“Alza al soglio”) that could be

nicely instrumental. Among these vocal works can be found some bits and

pieces of orchestral music, such as a non-sequitur ballet “suite” from

Ariodante. Porpora’s Overture to Polifemo of 1735 is a blend of old and new.

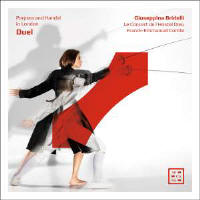

The slow dotted rhythms of the first section devolve into a rather

commonplace fugue, but the final minuet movement is quite modern. The performance by mezzo-soprano Giuseppina Bridelli is quite astoundingly good. We are used nowadays to these pieces of the opera seria being performed by countertenors, and these do an equally excellent job in recreating the world of the castrato. But there is equally room for pants roles, too, especially in the recording world. Here, she handles the often extreme vocal challenges with ease and fluidity, while having a warm and smooth tone for the slower arias and sections. The accompaniment by the Hostel Dieu is robust where needed, otherwise subtle enough not to interfere with the vocal pyrotechnics. All in all, this makes one enjoy an hour’s worth of opera seria.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|