Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer:

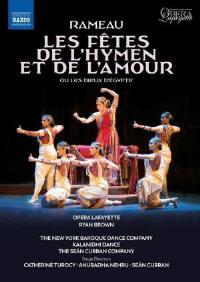

Richard Lawrence The Festivities of Hymen and Cupid was the second collaboration between Rameau and the librettist Louis de Cahusac. It began life as a ballet héroïque in three entrées, but before it could be submitted to the Paris Opéra it was taken over to form part of the celebrations marking the wedding of the Dauphin Louis (son of Louis XV, subsequently father of Louis XVI) to his second wife, Maria Josepha of Saxony. With the addition of a prologue, it was performed at Versailles on March 15, 1747. The original title was Les dieux d’Égypte (‘The Egyptian Gods’). Each entrée ends with the wedding of a god: Osiris, Canope and Aruéris (Horus) respectively. In the prologue, Cupid is depressed at losing his power to Hymen, the god of marriage; Hymen arrives, the two gods are reconciled, and they rejoice in the royal union. As in The Magic Flute, to take a familiar example, the Egyptian setting provided an opportunity for references to freemasonry: in the first entrée, Osiris brings enlightenment to the savage Amazons; the third features competitive games in honour of Isis. Les fête Although there are of course a lot of dances, they are not irrelevant interludes: Cahusac was skilled in devising what he called ballets figurés, dances that are intrinsic to the story. Some are short, played in rapid succession, which makes the frequent interruptions of applause in this production rather irritating. Sometimes the stage directions are followed, as when Cupid gives Hymen two golden arrows and they exchange torches; at other times the dancing seems abstract, but it’s hard to be sure as the camera often cuts away from the action to show the orchestra. The piece is fully staged, but with no scenery; conductor and orchestra are behind the singers and dancers, and the chorus – singing from scores – is in the balcony. Cahusac set much store by special effects. We don’t see the overflowing of the Nile, but Rameau’s depiction is vivid enough: scurrying descending scales in the orchestra, with a double chorus and two bass soloists. Nor, sadly, do we see Canope arriving in a chariot drawn by crocodiles. But the costumes – in a sort of timeless oriental style – are splendid. So, as ever, is Rameau’s writing for the dances and the choral numbers. The solos move seamlessly between recitative and arioso. The airs include a prayer to Cupid, ‘Veille Amour’, expressively sung by Ingrid Perruche, and a tender number for an Egyptian shepherd, ‘Ma bergère fuyait l’amour’, with musette accompaniment: Kyle Bielfield sings it gracefully, with lightly touched top Cs (sounding B flat). The cast boasts two more excellent hautes-contre in Aaron Sheehan and Jeffrey Thompson. Claire Debono occasionally sounds uncomfortable at the top of her register, but it’s not too serious. Ryan Brown, using the new critical edition by Thomas Soury, conducts the Opera Lafayette Orchestra and Chorus with both vigour and sensitivity. I wish I could be as enthusiastic about the balance of the recording: the orchestra sometimes fades away alarmingly, and the timpani are much too prominent. But overall this is well worth acquiring, to set alongside Le Concert Spirituel and Hervé Niquet on CD (Glossa, 12/14), which has the advantage of a booklet that includes the stage directions with the libretto. |

|