Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer:

Richard Wigmore

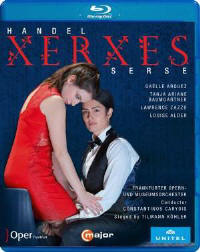

You might say

that this sour ending is the logical outcome of director Tilmann Köhler’s

vision, where the tyrannical, selfregarding Serse is capricious to the point

of instability, liable to turn vicious at any moment. In his Act 1 aria ‘Di

tacere’ he seems on the verge of raping Romilda, the object of his infatuation.

In the libretto and Handel’s music she is presented as the more serious of the

two sisters, unswervingly devoted to Serse’s brother Arsamene. Here she is as

flighty as her sister Atalanta, sexually attracted to Serse, as the booklet

photo makes clear. Things are further complicated by an unscripted attraction

between Atalanta and Arsamene. There are cat fights between the sisters; and at

one point we get a freeze frame of the ‘wrong’ pairings that evokes the

partner-swapping of Così fan tutte. It’s my guess that Così’s

ambivalences and problematic ending influenced Köhler’s whole conception of

Serse.

Yet while the

director plays up the elements of chaos (epitomised by the set’s progressively

trashed dinner table) and incipient cruelty, his modern-dress staging, complete

with video installations, is theatrically compelling and psychologically

convincing. In a uniformly fine, camerafriendly cast, all the singers throw

themselves with gusto into their roles and interact vividly. Amid the

production’s physicality, Köhler is unafraid of stillness at moments of

reflection, whether in the arias for the put-upon Arsamene – movingly performed

by the deep-toned countertenor Lawrence Zazzo – Amastre’s tender ‘Cagion son io’,

or the chastened Atalanta’s minuet song ‘Voi mi dite’, sung with poise and grace

by Louise Alder.

Earlier in the

opera Alder plays the minx to the life as she sharpens her claws in pursuit of

Arsamene. Her feeling for the Handelian line and sparkling coloratura are

matched by the American soprano Elizabeth Sutphen, whose wilful, strongly sung

Romilda is emphatically not a woman to be messed with. Tanja Ariane

Baumgartner’s powerful mezzo catches both Amastre’s outrage (not least in

a sulphurous ‘Anima infida’) and her vulnerability. Of the two basses, Brandon

Cedel sings with sturdy resonance as the worthy-but-dim general Ariodate, while

Thomas Faulkner’s amusing but unhammed Elviro irresistibly suggests a proto-Leporello

in his backchat with his master Arsamene. As the trigger of the opera’s

comic-cruel mayhem, Gaëlle Arquez rightly dominates, vocally and dramatically,

in the huge role of Serse, written for the castrato-fromhell Caffarelli. Her

warm, flexible mezzo soars easily above the stave, she phrases generously, and

brings a mingled fire and intense pathos to Serse’s central aria di bravura

‘Se bramate’. Constantinos Carydis sets languorous tempos in one or two numbers and can arbitrarily introduce solo strings where Handel prescribes tutti. For reasons I can’t fathom, Act 2 ends not with Romilda’s avowal of enduring love ‘Chi cede al furore’, here displaced to Act 3, but with Serse’s meditative ‘Il core spera’, which is then cut off in mid-sentence. But on the whole Carydis’s direction, always responsive to the singers, meshes well with the production – though the alert orchestra can suffer in the balance. If Köhler’s Serse leaves a slightly nasty taste in the mouth, I enjoyed it at least as much as Nicholas Hytner’s famous ENO production that balances elegant artifice with clever comic gags (Philips, 5/93). And for freshness and consistency of singing, the Frankfurt performance wins hands down. |

|