Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer:

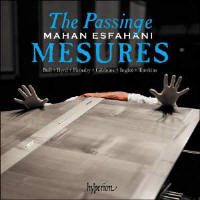

Philip Kennicott Two distinct personae emerge from Mahan Esfahani’s engaging foray into the English virginal tradition (with some possibly Welsh composers, too). One stresses the Renaissance connections of the music, the rigour of its polyphony and the grandness of vision worked out in the more elaborate works of Byrd, Bull and Tomkins. The other is lighter, more intimate and generally livelier, heard in small works by anonymous composers or charismatic, sometimes eccentric fare by Giles Farnaby. The contrast is heightened by Esfahani’s choice of two different instruments, one based on a two-manual Fleischer family harpsichord from the early 18th century and the other a deliciously reedy virginals copied from a mid-17thcentury instrument. In a booklet essay that is both charming and churlish, Esfahani sounds defensive about the use of the later, two-manual instrument. He could, he says, go into a long defense of this choice but, ‘simply put, I like how it sounds’. The choice speaks for itself, especially in works such as Byrd’s hexachord fantasy Ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, where the instrument’s expanded colour range allows the performer to contain the music’s magnificent sprawl of evolving variations into more contained chapters. He follows that work, a giant in the literature, with a lovely and trifling Scottish Gigg from a New York Public Library manuscript, and the juxtaposition is delightful. Played on the virginals, the anonymous Scottish gig is the sorbet after the grand meal. Esfahani’s playing is colourful and magnetic, the fingerwork in the more virtuoso works absolutely clean and articulate. The mean-tone tuning gives the accidentals and chromatic outliers in the more harmonically meandering of the pieces a wonderfully piquant twang. At the end of his essay, Esfahani says: ‘I encourage my pianist colleagues in particular to explore this repertoire.’ That sent me back to Glenn Gould’s occasional essays of music from this period, to be reminded of a very different approach: the scholar in his study, loving every twist and turn of the polyphonic lines, the music hovering in the air like some perfectly sculpted object, stately and slow. That isn’t at all how Esfahani plays it. Here it is robust, vital and exciting, and whatever tendency to philosophising the artist may have is left to the booklet notes. |

|