Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

Recording of the month |

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

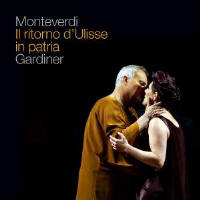

Reviewer: Alexandra Coghlan ‘Where Gardiner’s performance comes into its own is in its ability to absorb extremes into a coherent whole’ John Eliot Gardiner’s recordings of Orfeo and L’incoronazione di Poppea both stretch back several decades but it has taken until now for the conductor to tackle the composer’s great paean to married love, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria. The result is both the end of a cycle and the beginning of a new era, clearly related to Gardiner’s earlier accounts but refined and refashioned for another age and audience. Monteverdi’s 450th anniversary gave us a year of musical celebration but no tribute was more elaborate than that by Gardiner, who assembled a hand-picked ensemble of soloists to tour the composer’s three surviving operas internationally over the course of more than six months with his Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists. In the concert hall these semi-stagings were arresting experiences with the orchestra at their heart, the drama emerging organically from the close relationship between singers and It’s an approach that lends itself naturally to disc, and this account (recorded live towards the end of the tour in Wroclaw) has an appealing energy and ease. Recitatives flicker and spark with detail, the repartee of the court, the blandishments of the young lovers, the pronouncements of the gods and the halting reconciliation between husband and wife each coloured distinctly. Instrumental textures are spare and speeds swift, and there’s a welcome sense of narrative drive through a story that lacks the easy sensation of Poppea or the episodic structure of Orfeo. It’s a commonplace to point to the Shakespearean quality of Ulisse, but the opera’s broad dramatic lens – its colliding of high and low, of broad comedy and finely drawn psychology – and its back-and-forth, text-driven drama is truly that of a sung play. Where Gardiner’s performance comes into its own is in its ability to absorb these extremes into a coherent whole. Text is king, but it’s the rhetoric of the English Baroque Soloists that really counts: sensitive to every inference and shift of mood, it’s their instrumental inflections and colouring that fills out the silhouette of the sung drama. The shy beauty of the recorders that support Penelope’s timid closing attempt at aria (compared to the forthright exuberance of those that accompany the reunion of Ulisse and Eumete), the frothy, suddenly self-conscious detail of the realisations that accompany the suitors, the crisp authority of the strings that support Minerva’s pronouncements – all are part of a single, richly drawn world.

Hana Blažíková is a radiant Minerva, while Gianluca Buratto brings charred blackness and depth to Nettuno and suitor Antinoo. Anna Dennis is all warm sensuality as Melanto, though her pairing with Zachary Wilder’s Eurimaco sounds almost too beautiful, too poetic for these earthiest of lovers. There’s a pleasing simplicity to Francisco Fernández-Rueda’s Eumete, and the scene with Zanasi’s newly revealed Ulisse that closes Act 1 is one of the most touching moments of this account – a last breath of outdoor innocence before we find ourselves trapped in the fetid intimacy and affectation of the court. Iro can be a problem on disc. The vocal burlesque and caricature needed to propel the glutton’s scenes on stage can jar in the inevitably music-privileging context of a recording. There’s plenty of the grotesque to Robert Burt’s performance. Wheedling, whining and storming his way through his Act 3 lament, he’s an uncompromising figure, but never less (or more) than human – pitiable, rather than horrifying even at his blustering extremes. All the old dramatic clarity of Gardiner’s Monteverdi accounts are here but it’s as if the camera has zoomed in. For the first time we hear husk and breath as well as melody, our ears drawn constantly to the subtlest detail of instrumental shading or vocal colour. There’s a sense of exhilaration, of risk, to this musical proximity. Standing inches from a musical oil painting, you can suddenly pick out the brush strokes that energise the whole. There are more classically beautiful accounts of Il ritorno d’Ulisse available, but perhaps none with quite so much life.

|

|