Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

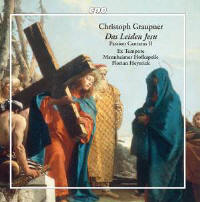

As I have noted several

times previously, Christoph Graupner should probably be known as one of if

not the most prolific composer of German Protestant cantatas during the

first half of the 18th century. He composed these fluidly and rapidly during

his rather long life, and though his reputation thereafter was obscured by

his music being absorbed into the personal library of the court at Darmstadt

(and the subject of a lengthy lawsuit), in recent years he has emerged as

one of the pivotal figures along with Georg Philipp Telemann in the

transition from the Baroque to the Classical style. The cantatas, composed

over many decades, exemplifies this tradition, but given the immense body of

work, a resurrection will be a long and perhaps tortuous process. Moreover,

the inevitable comparison with the better-known corpus of Johann Sebastian

Bach pits an icon against one of his colleagues, forgetting that Graupner

was also in the running for the Leipzig church job that Bach eventually got.

I have reviewed several discs

of Graupner’s cantatas, and my general observations that he was fully aware

of the changing tastes and styles of his time (he was two years older than

Bach and died in 1760), had at his disposal a proficient and

well-disciplined court orchestra, and was not afraid to experiment in his

compositions, are maintained with this disc. This is the second one

featuring Passion cantatas to texts by Johann Conrad Lichtenberg, a

theologian in Darmstadt with ties to both the court and local Lutheran

churches. His works include three cycles of Lenten texts, and since Graupner

was the composer in residence, he was assured of at least his setting for

Duke Ernst Ludwig. Indeed, composer and librettist were related by marriage,

each having married one of the sisters of a local pastor. The excellent

booklet notes by Marc Roderich Pfau title the works in this series as

“mini-Passions,” but that is perhaps stretching the designation. Each work

is a rather conventional cantata, with an opening statement (the Dictum,

often couched as a chorale or larger chorus), several arias (and

recitatives), and a chorale finale to solidify the message. The usual vocal

quartet are soloists, and given the solemnity of the subject matter, it is

not surprising that Graupner chooses a rather conventional orchestration of

woodwinds, eschewing the brass. The three works here begin with a cantata for Oculi Sunday, the third Sunday in Lent. It focuses on the betrayal by Judas and how friendship (or in this case discipleship) is vital to the redemption. Graupner begins the work with a Dictum, a mournful lament ably performed by tenor Lothar Blum that dissolves easily into the following accompanied recitative. The first aria, for soprano and performed by Annelies van Gramberen, is a gentle minuet in a thoroughly modern empfindsamer Stil. The strings walk slowly, and the voice has a bit more coloratura than one might expect. The next aria for bass has a rather complex texture in which the lines tumble over themselves, but are not contrapuntal. As always, the work ends with a chorale, “Herr, lass Dein bitter Leiden,” that has a solemn and even funereal accompaniment. The cantata for Good Friday, “Die gesegnete Vollendung,” is slow and deliberate in the opening chorale, with soft flutes and a chorus part that appears haltingly. The solo flute lines (along with a solo violin) in the first aria paints a picture that is at once reflective and vacillates between pensive thought and a major key pastoral. Given that the subject is death, one might consider this a bit too modern for the contemplative subject matter. The Dictum is pure Baroque, almost reminiscent of Henry Purcell with echoing flutes and oboes that have a rather short set of interspersed moments with the chorus. No real counterpoint here, either. When “all is done” (as the second aria states), the rather playful theme dissolves into a moment of thoughtful focus before returning with a rather uplifting tone. The final cantata for the Annunciation has a slow introduction that has ponderous chords that are overlain by flutes and oboes with a pastoral tone. The first duet is a quite modern operatic aria that seems more Handelian. The final aria has some rather intriguing syncopations in the main theme. The

ensemble work is rather on the thin side, with the group Ex Tempore, from

which the soloists are taken, being a double quartet. Dominik Wörner’s bass

is light and expressive, while both countertenor Marnix de Cat and tenor

Lothar Blum are quite adept in their phrasing and emphases that brings the

music to life. Only soprano Annelies Van Gramberen can be a bit shrill in

her tone, while her colleague Jana Pieters has a more well-rounded voice.

The Mannheimer Hofkapelle performs one on a part, but the recording makes it

seem like the ensemble is larger, with a nice richness and depth. The tempos

are all variable enough to bring out Graupner’s subtleties, and the

intonation is excellent. In all, this is a worthy addition to the canon of

Graupner’s cantatas, and while the subject matter is perhaps a bit more

solemn than the time when this is being written (in September), it

nonetheless speaks to the variety and craftsmanship of the composer’s music.

Well worth obtaining as an alternative to Telemann and Bach. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|