Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

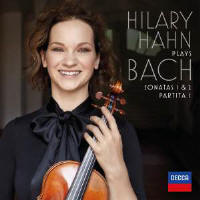

Reviewer: Huntley

Dent

Of all the ways a performer

can approach Bach’s treasured Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, I’d

never expect a performance of gleaming strength to come from Hilary Hahn.

That’s the initial surprise of her debut on Decca, all but contradicting my

expectation that she would be refined and a bit reserved. But was she ever

that reserved? Image can interfere with reality, and Hahn’s sylph-like

appearance onstage never indicated a slight interpreter. I decided to go

back to her first album for Sony from 1997, which contains Sonata No. 3 and

Partitas Nos. 2 and 3—added to this new release, she has now completed the

cycle on two separate labels over a gap of some 20 years.

Because they lack markings for

expression and dynamics and have only a scattering of general tempo

indications, the Sonatas and Partitas raise the fluid question of how to

play them as music rather than notes on the page. Some violinists prefer

purity, choosing not to interfere with their own interpretative ideas. I

don’t see how this is defensible; Bach the performer wouldn’t have treated

Bach the composer as a kind of print-out of black dots on a page. Nor is the

violin remotely similar to a harpsichord, with its mechanical action and

inability to play legato, crescendo, and diminuendo. Most violinists choose

to express their own ideas in these pieces, and among the most personal in

recent years have been Sergey Khachatryan, whose style is charismatically

Romantic, and Christian Tetzlaff, whose third account of the complete

Sonatas and Partitas is intense and probing to a remarkable degree (see my

review in Fanfare 41:3). Twenty years ago a 17-year-old female violinist with Hahn’s pure sound, confident technique, and mature musicianship was the American equivalent of Anne-Sophie Mutter. But Hahn didn’t trade in on glamour, and she wasn’t prone to the mature Mutter’s interpretative boldness—or eccentricities if you disapprove of them. What she had was constant exposure to Bach’s solo violin works, at least one movement of which, she says in a personal note to this release, she had played every day since she was nine. That first Sony album indicated a performer who had the assurance and technique to enter the top tier of the (male-dominated) profession. Otherwise, Hahn’s Bach was on the pristine side, very cleanly executed but without variation in tempo or dynamics to any marked degree. To be impressed, you had to value those qualities primarily, along with a tonal production of impressive evenness.

Bach was revisited in 2003 on

a DG album of the violin concertos, which I find more appealing because less

reticent in terms of expression. Hahn retained her basic respect for the

absence of markings but had loosened up enough not to sound as dry as

stubborn literalists can be. Her clean, bright, buoyant performances were

delightful, in fact. Today, on the verge of turning 40, Hahn is expected, by

me at least, to unfold a richer, more varied landscape in Bach’s solo violin

works if she wants to make a real mark.

She’s accomplished this, I

think, adding the panoply of modern violin playing—a wide tonal palette,

legato, crescendo, diminuendo, and so on. No longer reticent or purist, she

now has something personal to say in music that always mirrors a performer’s

personality, even when that personality is hiding behind purism. Hearing her

bold attack in the opening Adagio of Sonata No. 1, and the way she digs into

the G-string in the Fugue, I heard a new approach unrecognizable in the

younger Hahn. The Siciliana is shaped very personally, by which time I

appreciated that far from being a sequence of dances and abstract musical

forms, Hahn regards each movement as a separate artistic creation, obliging

her to unlock the secret of how to make it sound unique. I can’t think of a greater challenge—and risk—which leads to the highest praise if an artist succeeds. To be truly memorable in these pieces, you have to love to deliver soliloquies. That wasn’t the case with Hahn on her first disc, but now it is, making her complete cycle the most uneven on disc, I imagine. As for specifics, I have few to offer, because to do justice to her interpretation, I’d have to describe every movement individually. Suffice it that the beautiful tone we expect from Hahn is present, and she pours out her technique unstintingly. Nothing feels casual or routine. Unlike Tetzlaff, who sometimes chooses extreme tempos and draws us into a very inward-looking space, Hahn’s pacing is within the usual range, and she varies the mood between extroversion and introversion. Such an eloquent, accomplished reading deserves a strong recommendation. The recorded sound is perfectly clear and natural, with enough ambience to provide some air around the notes. Hahn needs to complete the cycle in her mature style, which I hope she will do. This second half is totally absorbing. She tells us in the booklet that solo Bach “is still, by far, the repertoire I’ve played the most.” It shows. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|