Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

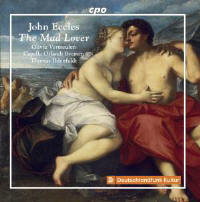

van Boer One of the least-recorded genres of music tends to be that written specifically for spoken drama. During the 18th century (and earlier) no play would have been thought complete without incidental music, as this was seen even as early as Shakespeare to have been part of the entertainment of the stage. During the Restoration, one must remember that Henry Purcell devoted much of his considerable energy to writing insertions for plays, and even as early as 1679 he was writing songs for John Playford to use in the theater. For his short career, he composed frequently for the Dorset Street Theatre, and his music includes the semi-operas that have been recorded frequently, such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But he also wrote music for numerous plays, ranging from short interludes to insertion songs, and his successors and colleagues wrote copious pieces for the Theatre Royal and other venues. Despite the popularity of these works (and their national focus), they were soon eclipsed by the Italian opera seria, and for several decades thereafter they fell into obscurity. Even today, this legacy relies on the occasional Matthew Locke or Henry Purcell work, but numerous other composers’ works have been ignored. Here we have an attempt to rectify this situation by providing incidental music by two of his contemporaries, John Eccles (1668–1735) and a German import, Gottfried Finger (1660–1730). Both were associated with the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre, which was formed in 1695 (ironically the year of Purcell’s death). Here, they collaborated with dramatists such as William Congreave in providing music for various plays. This disc includes both tunes and airs for various performances produced there; the vocal part was meant for Anne Bracegirdle, whose acting and singing were deemed some of the best of the age. As these were often generic works, they appeared in several plays, and in keeping with their function, they are all quite brief and expository. The Capella Orlandi Bremen has focused on three of these, Finger’s Love at a Loss and Alexander the Great. Eccles, however, contributed a number of pieces for Bracegirdle for each of these. Each of these has the traditional overture for strings and oboes, beginning with a stately Adagio followed by a contrapuntal piece that seems most dance-like rather than strict. The Overture to the latter is lively and bright, and one can easily mistake it for a Handel piece. In Love at a Loss, Finger supplies several short dances, such as the Round O, in which a gentle chaconne bass outlines a soft and pensive tune. His entry for Alexander could have been written by Handel as it reminds one of the Queen of Sheba in Solomon. Eccles provided a number of arias for each of these two plays, specially written for Bracegirdle. These are mostly drawn from other plays, used here in a more generic fashion. “I burn, my brain consumes to ashes” is a sort of quasi-recitative that suddenly erupts into brief moments of coloratura. Momentary echoing phrases between the continuo and voice add dramatic power as the music proceeds into a strophic aria. The complete Eccles work, The Mad Lover, is a revived work from 1647, a masque that takes its content from Ovid’s tale of Acis and Galatea. The music is simpler, with an orchestra overture for strings only that is thickly textured and far more contrapuntal than the usual work. The lilting “Come, ye nymphs” could have been composed by Purcell with its lyrical line that emphasizes the nature of the English language, and it is followed by an air that features soft pizzicato strings, almost ethereal. This contrasts with the lively jig with its swirling recorder solo. The aria “How lovely sweet and dear” is almost an anachronistic lute song that might have been composed by Locke or even Dowland (safe for the modern cadences). The performance by the Capella Orlandi is smooth and polished. Even though one-on-a-part (which probably mirrored the original performance circumstances), the textures tend towards the lush side, and of course the intonation is precise and the sound clear. Olivia Vermeulen’s voice is bright and cheerful, lending exactly the ambience that this simple and direct music requires. In short, this is an excellent disc and gives an example of the musical entertainments that preceded the rise of the Italian opera in the English capital. For an hour’s whiling away, heartily recommended. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|