Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

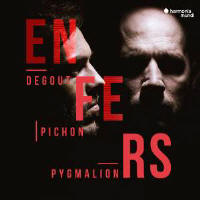

Encountering this disc, one is

apt to exclaim, “Ah, another topical recording cobbled together in a clever

fashion.” As the booklet notes state, conductor of the early music group

Pygmalion, Rafaël Pichon, has concocted this work to represent a parody of

the Requiem Mass, though the title reference to Hades more reflects the

sinister illustrations, with faces poking out of the darkness in what is

supposed to be a frightening manner. I presume that this sort of hocus-pocus

is evocative, but the layout, each section conforming to a part of the Mass

for the Dead, is filled with the expressive music drawn from several works

by Jean-Philippe Rameau and Christoph Willibald von Gluck, two of

18th-century Paris’s major operatic composers. One finds the excuse in a

parody Requiem recently uncovered in the Bibliothèque nationale of Rameau’s

pieces, though music from this appears only sporadically throughout. The

sources are Rameau’s Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Dardanus, Hippolytie et

Aricie, as well as the ballets Les Boréades and Les Surprises de l’amour,

both of which are hardly hellish. Gluck, though, has a better claim to the

underworld, with excerpts from Orfeo, Iphigénie en Taride, and Armide. There

is even an insert from Jean-Féry Rebel’s Les Éléments entitled “Chaos.” Such themed recordings may have a marketing appeal, but can easily go awry as cohesive programs. Here, though, the rediscovered parody Requiem lies at the core of the disc, and given that it is too short to stand on its own, perhaps embedding it in a cocoon of other miscellaneous works along thematic lines makes some sense. Most of the pieces chosen are powerful and often violent. Rebel’s “Chaos,” for example, runs amok with growling percussion alternating with swirling tremolo strings and fragments of melody, all fitfully and frighteningly performed by Pygmalion. And this is just the Introit. It does set up the funereal opening of the Requiem nicely, though, and as the orchestra intones the solemn chords after a furious percussion introduction, the chorus enters as softly and angelically as one could wish. The harmonies are sometimes gentle and sometimes quite dissonant, mitigated by the softer vocal setting. The Kyrie is often thought of as an opportunity for a fugue, but here the anonymous piece has a more fulsome tone, a flowing aria that is followed by a choral refrain. The end of the section with a ballet Loure is a bit anticlimactic, but serves to transition into the next section, a misplaced gradual Domine Jesu Christe normally found after the Sequence. The flashy duet from Armide by Gluck gives an unsettled feeling, while the anonymous gradual is a gentler contrapuntal bit with virtually no emotional power involved in the pastoral setting.

Of course, the Sequence Dies irae is the core of any Requiem Mass, and as such is perhaps the section that inspires the most interesting music. Here it begins appropriately with the Furies from Gluck’s Orfeo, with its solemn chordal announcement of the Underworld. This is followed by a trio of excerpts from Rameau’s Zoroastre, one of his most modern and powerful works, all of which are suitably gripping musically with colorful orchestration featuring rolling drums. Apparently the anonymous paraphrase omits this crucial portion, which probably would have been beyond the capabilities of the arranger, even given that ample possibilities exist among Rameau’s works (just not Castor et Pollux). The offertory follows this with a series of more solemn pieces that are less powerful but more introspective. The anonymous Hostias rocks along with a flowing compound meter like a stream, complemented by other Rameau arias that are equally as slow moving and placid. The final Communion suddenly changes mood with the floating dance of the Elysian shadows from Orfeo and a repeat of the opening anonymous Requiem in aeternum.

As for the performance, it certainly exceeds expectations in terms of power and precision. Pygmalion’s conductor Raphaël Pichon knows how to interpret this sort of music, and the result is a fine performance by the instruments with exceedingly precise nuances. The percussion is forceful as needed, the woodwinds ethereal, and the strings cohesive in tone. Stéphane Degout has a nicely flexible voice, dark when needed and soaring in the higher ranges. He is joined by a number of colleagues, all of whom blend well in their ensemble numbers and yet are clear and present in their solo roles. The only issue is that the anonymous paraphrase Requiem is one of those works that really is solely of historical interest, as it lacks the core of the Sequence (the Dies irae) and is bland in the other movements in comparison with the actual works by Rameau and Gluck (not to mention the fiery Féry). Still, if one wants a programmatic disc of music of this age, it might suit as a taste of the power of French opera of the time. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|