Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

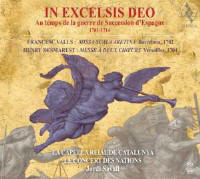

Brenesal This album focuses on two works composed within a few years of one another, though Valls’s Missa scala aretina (1702) had no discernible influence on Desmarest’s Messe à deux chœurs et deux orchestres (c. 1704). Also included in the set is the Batalla imperial attributed to both Cabanilles and Kerll, as well as three “ancient songs,” one performed in both instrumental and choral clothing. Francesco Valls (or Francesc Vals, his original Catalan name, which is given equal time in the album’s liner notes) is best known today not for his music, but for a huge row that erupted over his use of an unprepared ninth chord on an imitative entry during the Mass’s Gloria, in the second soprano part at the words miserere nobis. Before it faded into obscurity, dozens of musicians had commented in writing over the matter. As with so many similar artistic wars over the ages to this day, however, it wasn’t as much about the music as it was a matter of affirming patronage, and taking sides in heavily polarized factional politics on regional, national, and international levels. I find the work as a whole recalls comments made by Bertil van Boer in his review of Valls’s Lauda Jerusalem (Fanfare 38:6; Lauda 014), when he refers to “a staid chorus with a pair of high trumpets … the voices weave a contrapuntal tapestry around a solo trumpet.” This same squarely phrased, endlessly celebratory, pound-the-tonic-into-the-ground feeling pervades the entire work, even the Sanctus. To be fair, there are moments of interest: the Gloria’s dance-like Cum Sancto Spiritu, where Valls celebrates in a melismatic passage of his Amen with what we would call an enharmonic progression; the tonally upsetting ascendant leaps that mirror the text at Et ascendit in coelum in the Credo; and the chromaticism of the Agnus Dei. But that same movement vies with, and ultimately loses out to, the monotonous triumphalism that offers little in the way of transformative or expressive interest. Desmarest’s Mass, on the other hand, is a work of varied and sustained inspiration. James R. Anthony notes that he thought “more polyphonically than any other composer of his generation in France,” and the brilliant fugue that concludes Desmarest’s Gloria is one fine example of this. Nor is he above experiment for expressive purposes, moving from the duet for soprano and paired flutes in the Benedictus section of his Sanctus to an Hosanna in excelsis that deliberately confuses all sense of beat and key in order to convey enthusiasm beyond the limitations of self. For the rest, Jordi Savall includes the Batalla Imperial (either by Cabanilles or Kerll), as well as three songs described simply as ancient, one in versions featuring instrumentals, and vocal with instrumentals. In their current arrangements by Savall, with richly massed orchestra and unified choral forces, they do sound more like movie soundtrack material. However, the instrumental forces of Le Concert des Nations and Hespèrion XXI are uniformly excellent. La Capella Reial de Catalunya’s massed choral singing is fine; however, its soloists are variable in quality. Several demonstrate fine agility, strong breath support, and solid enunciation, but others can hardly be heard—and when they are, they reveal periodic pitch issues or an inability to span the long lines of Valls’s writing in particular. There are a very few instances of slightly delayed imitative entries, which may be due to taking too lengthy a breath at the end of earlier passages. (An instance of this in fact occurs in that same “miserere nobis” of Valls’s Gloria, mentioned earlier.) It doesn’t help that the engineering favors the instruments, especially the bright trumpets and lower strings, so that much of the details of the contrapuntal tapestry in both Masses is lost. This is especially damaging in the magnificent fugue of the Cum Spirito Sanctu section that concludes Desmarest’s Gloria. Perhaps this suits Savall’s vision, for certainly he finds every opportunity to emphasize orchestral color and splendor in these works. Some interpretative details may strike the listener as surprisingly modern—such as the word “Kyrie” in at the start of that movement in Valls’s Mass, lengthened to such a point as to bring Beethoven and later Romantics to mind. Still, the performances are keen and generally well wrought, though I prefer the clarity of the Desmarest Mass featuring Olivier Schneebeli and Les Pages & Chantres de La Chapelle (Virgin Classics 45416; Fanfare 24:5). However, the latter’s soloists are also uneven, so it’s up to you. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|