Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: Alia Vox |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: John

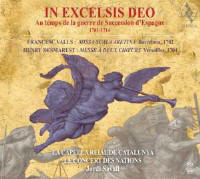

W. Barker Among other things, this is one of those “where-do-we-put-this?” releases.

It is one of Savall’s CD Book

ventures, but without the book-size album, though it has a thick, 253-page

paperback volume (with multilingual essays) as its “booklet” in the standard

CD album format. It is presented as another of Savall’s historical

panoramas, with the title of “In Excelsis Deo: In the Time of the War of

Spanish Succession, 1701-1714”. “In the Time of” is the trick phrase here,

for the two major works presented have nothing directly to do with that war,

even if composed in the time period. The combination of those two works was

made into a program performed in public concerts that Savall gave in his

busy year of 2016, and this comes from the program given at the Royal

Chapel of the Versailles Chateau in July of that year. In point of fact, the

program is as much a celebration of Savall’s rich involvement with the

Versailles Chapel over the years as of anything else.

Francesc [or Francesco] Valls

(1671-1747) was the most important of early Catalan composers. Since

Catalunya as a region supported the Hapsburg claims to the Spanish crown,

Valls is sucked along with that. As cathedral director in Barcelona, he

produced a great deal of sacred music, bits of which have been recorded over

the years. He composed some nine Mass settings, of which by far his most

celebrated work is this 11-voice masterpiece that dates from 1702. In it his

forces are divided into four distinct choirs—three of solo and choral

singers and one of instruments (two violins, doubled by oboes, cello, two

organs, harp, and two trumpets with timpani). Valls gave the work its “Scala

Aretina” title because he used the traditional hexachord of Guido d’Arezzo

as a cantus firmus. The work actually provoked violent controversy over the

composer’s counterpoint and his introduction ofan unconventional dissonance

at one point. To our ears it is full of beauty and imagination. So far as I

can find, there have been three earlier recordings. A rather ponderous one

led by John Hoban in a CD reissue (CRD 3371: S/O 1995) was followed by a

1993 recording (combined with Biber’s Requiem), again with large choir but

with period instruments, led by Gustav Leonhardt for German Harmonia Mundi

(77277: N/D 1993). Most recently, we have a recording of this Mass, plus

some of the composer’s shorter sacred works, made under Albert Recasens (Lauda

14: M/J 2015): a very stripped-down rendition, one performer per part. Those predecessors may not all be available, but Savall’s performance does not entirely eclipse them. His vocal forces number 26 singers and 24 instrumentalists including flutes and bassoons. Savall captures the lyrical sweep and contrapuntal cleverness of the work, but the total seems a bit blurred and dense, perhaps owing to the Versailles Chapel acoustics.

Since Valls was a Catalan, and

his Mass takes barely 35 minutes, there is space for fillers. Savall takes

advantage of the national connection—and perhaps even inspiration from the

recent Catalan separatist movement— to throw in five short works, mostly

Catalan patriotic songs that he has recorded before in his own arrangements.

Almost buried here in the fuss

over Valls, Henry Desmarest [or Desmarets] (1661-1741) has his say in the

second disc. He was a prolific composer of both theatrical and sacred works.

In his colorful and disruptive life, he really served as a partner to

Lalande in developing the French Baroque motet. A number of the shorter

sacred ones have appeared in several releases, but this is the first

recording of his ambitious treatment of the Mass, his only one. King Louis

XIV, the composer’s employer at the time, preferred motets over full Mass

renditions in his chapel. Nevertheless, the King apparently did attend a

performance of this work, at some time around 1704. Again, this Mass has

absolutely no connection to the War of Spanish Succession, even if Desmarest

did, around 1701, begin a few years in service to the triumphant Bourbon

King of Spain, Philip V.

Stylistically, this unique

Mass by Desmarest might be understood as a blending of French and Spanish

Baroque elements. It is an extraordinarily big work, lasting a full hour.

Like Valls, Desmarest divided the major items in the Ordinary into many

movements, mostly brief: thus, the Gloria is in 7 sections, the Credo into

no less than 18! (By comparison, Valls divided his Gloria into 5 sections,

his Credo into 6—and omitted the Benedictus.) That microcosmic choice by

Desmarest has its negating effects, as the mostly little bits process by in

relentless continuity. There are beautiful moments to emerge, and the

dialogs between the two groupings of performers can be interesting.

Nevertheless, the work seems to lack an overall unity. I have to say that I

found it in toto a bit tiring and even self-defeating. The performing forces are 25 singers and 13 instrumentalists here. Missing parts in the surviving scores have had to be recreated. Savall labors admirably to make this whole business work, but I emerge from it rather disappointed — essentially the composer’s fault, not the conductor’s.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|