Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

International Record Review - (11//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

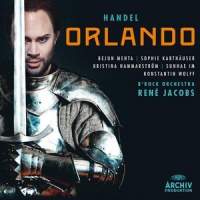

Archiv

ARC4792199

Code-barres / Barcode : 0028947921998 (ID423)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

Orlando loves Angelica, who loves Medoro, having cared for his battle wounds, but he's also loved by Dorinda. Angelica's rejection and supposed betrayal drive Orlando mad, but his madness is cured by the magician Zoroastro, and he and Dorinda both eventually accept the union of Medoro and Angelica. That's Orlando, in a nutshell. Handel's thirty‑first stage work (1733), written for the greatest artists of the King's Theatre (alto castrato Senesino and soprano Anna Strada del Pò), the piece has been performed with increasing frequency of late, given the abundance of superb Baroque interpreters and the fact that, with five singers and no chorus, it's a manageable work for any opera company ‑ that is, if a technicalIy feasible solution can be achieved in creating Zoroastro's magic effects onstage. Whether on CD or in the theatre, I've encountered Orlando a good deal in the past few years and, being a Handel enthusiast from way back, I want very much to adore it. Yes, many individual numbers give pleasure ‑ there's no reflective aria in Handel more dulcet than Medoro's 'Verdi allori', no upbeat number more lovable than Dorinda's 'Amor è quel vento'. The grandeur of Zoroastro's opening pronouncement impresses. The title character can ensure an ovation with his martial‑style showpiece. His mad scene and the extreme contrasts of his Act 3 aria 'Già lo stringo' boast a musical adventurousness that stands out strongly in the entire Baroque repertoire. Still, I find myself constantly jotting down standard adjectives such as 'sweet', 'vigorous', 'pleasant', while never being truly grabbed as I am in every aria of the most intriguing and complex Handel characters ‑ Giulio Cesare and Cleopatra, Ariodante, Rinaldo, Partenope. It's frustrating to feel no lure into the emotional content, although I've come close with Arleen Auger's matchlessly feminine Angelica (L'Oiseau Lyre), and with Patricia Barden (Erato), who presents Orlando's madness with scalding intensity.

In this new recording, René Jacobs's debut on Archiv, the rhythmic precision that has made this conductor's operatic recordings so invigorating is again evident everywhere. One's attention is riveted with the first notes of the Overture, thanks to the astringent string timbres of B'Rock Orchestra Ghent (the really impish‑sounding flutes are also particularly enjoyable). I don't find the ensemble's sound in itself as truly alluring as what one hears from the best French and British groups, but of B'Rock's virtuosity there can be no doubt whatever (captured in Archiv's notably clear sound). Usual elements of Jacobs recordings, such as an excessively 'busy' continuo contribution and a variety of sound effects, are present ‑ I could do without the latter in nearly every instance.

Jacobs, as always, has coaxed considerable dramatic involvement from his cast, who project the text with consistent clarity throughout (almost disconcertingly at times), whether in aria or extensive recitative. The five singers also possess the necessary agility, and whether their ornamentation was given them by their conductor or is their own creation, they project it with flair.

Orlando is for alto rather than mezzo, requiring exceptional thrust in the lower-middle range that most countertenors are hard‑pressed to produce. Bejun Mehta has it, and he's exciting whenever singing 'full out'. He moves smoothly above and below the lower break, and his coloratura is easily dispatched. The florid passages, however, emerge as simply that ‑ moments of impressive vocal display ‑ rather than enhancement of his actual characterization. The voice can turn grainy, the legato somewhat languid, and there are distinctly awkward moments at the top. Mehta does handle the mad scene with the requisite musical and dramatic intelligence, managing the crucial transitions especially well.

Sophie Karthduser (Angelica), previously ravishing in Jacobs's Harmonia Mundi

recording of Mozart's Lafinta giardiniera (reviewed in November 2012), remains an exceptionally graceful phraser. She also brings notable colouristic variety to this role and wide range (even bringing some gutsy chest voice into one of her cadenzas). At lower dynamics she still sounds delectable, but too often her tone loses its centre. The performance remains appealing nonetheless, even if neither the purity of Auger nor the warmth of Karina Gauvin (Atma Classique) is present.

Handel's chief requirements for his secondary alto roles are usually mellow beauty of timbre and quiet, unfettered sincerity of address. Medoro is one of those roles ‑ written for female voice rather than castrato ‑ and the music precisely fits Kristina Hammarström's voice and style. Although definitely a mezzo, she offers plum‑luscious but never excessively 'fruity' tone, deployed with exquisite elegance. Her role doesn't otter much dramatic scope, but Medoro's ardour emerges strongly.

The seconda donna, Dorinda, is quite important here, and it's a challenge to any soubrette to maintain appeal in the role throughout. Amanda Forsythe (Atma Classique) does so effortlessly, but Sunhae Im works too hard to make something of every line. The Korean soprano offers bright sound ‑ quite thin on top ‑ that is too much of a good thing. She does her best to vary it (the gentle 'Se mi rivolgo' early in Act 2 is generally lovely), and there are some moments of true adorability, as in Dorinda's incredulity at 'Orlando? II gran Orlando?' in Act 3.

One needs

a 'rolling' quality of tone and grand‑scale utterance for Zoroastro, sung by

Konstantin Wolff with admirable confidence and in a hearty timbre more

attractive than that of David Thomas (L'Oiseau‑Lyre) and fuller than that of

Harry van der Kamp (Erato). The martial‑style coloratura and the relishing

of text are especially enjoyable in 'Lascia amor'.

Unlike the other versions on CD, Archiv's takes two discs rather than three.

The detailed synopsis is invaluable as is Reinhard Strohm's booklet essay.

As to a recommendation: despite all the assets of the new recording, I'll

still return first to Erato's performance, with William Christie brilliantly

leading Les Arts Florissants and a cast led by two impeccable Handelians,

Patricia Bardon and Rosemary Joshua.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews