Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|||||||

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|||||||

|

Reviewer: Graham Lock In the New Grove Handel Winton Dean divides Handel’s opera into three types: the heroic and the magic encompass nearly all the better known works, but there’s a third, unnamed group, often overlooked, that, he says, ‘embraces serious emotion, comic or even farcical situations and an element of parody’. Agrippina (Venice, 1710) and Partenope (London, 1730) belong to this category, which should perhaps be called ‘anti-heroic comedy’, since that’s how Dean describes Agrippina and how Jonathan Keates, in his Handel biography, describes Partenope. Curiously, the operas share a few other unusual attributes: they each feature a pair of female characters as their leading protagonists; both include a variety of ensembles and numerous short arias; and they each boast a fine libretto. Where they differ markedly is in the tone of their humour: Agrippina is a dark, droll satire on political and sexual intrigue, whereas Partenope is a breezy Baroque rom-com about love’s illusions and the ‘intermingled pain’ that leads to personal growth.

Laurence Cummings’ new Agrippina, recorded live at the 2015 Göttingen International Handel Festival, is a bit of a damp squib, less well sung than John Eliot Gardiner’s benchmark 1997 Philips release, less vivacious than René Jacobs sparkling 2011 recording for Harmonia Mundi. Ida Falk Winland’s flamboyant, feisty Poppea is the set’s main attraction, while Ulrike Schneider is a forceful if unsubtle Agrippina. However, Christopher Ainslie’s bland Ottone and João Fernandes’ wooden Claudio are disappointments, especially in comparison to Michael Chance and Alastair Miles for Gardiner. Cummings, like Jacobs, omits Giuone’s appearance in the final scene – a pity, because her aria praising the characters’ ‘faithfulness’ adds a last, delicious shaftof irony that undermines the apparently happy ending.

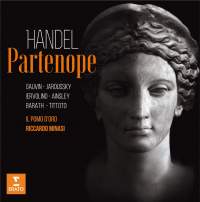

Riccardo Minasi’s all-star Partenope is a far more lively and engaging affair. Recitatives are dispatched with speedy élan, while both singing and playing are superbly expressive. Karina Gauvin’s assured Partenope is matched by Rosemary Joshua on Christian Curnyn’s rival Chandos recording, but in all other respects Minasi’s expansive approach and pulsating energy trump the competition. He also scores by including Armindo’s haunting aria ‘Bramo restar, ma no’ (from the 1737 revival), beautifully sung here by soprano Emöke Barath. Philippe Jaroussky’s soft, sensuous countertenor makes him an ideal Arsace, while mezzo Teresa Iervolino is a formidable Rosmene, especially when accompanied by clamorous horns in her boisterous hunting aria, ‘Io seguo sol fiero’. It’s just one of the many glorious tunes so vividly brought to life on this triumphant recording. Viva Partenope, viva Minasi!

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|||||||