Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 37:3 (01-02/2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

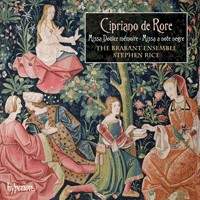

Hyperion

CDA 67913

Code-barres / Barcode : 0034571179131 (ID352)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

Cypriano de Rore (c.1515–65) is well known among the first generation of madrigalists, so this program of two Masses framing three motets focuses on a less prominent part of his output. A Fleming who spent most of his life in Italy, he is first known at Brescia in 1542. Four years later he was in Ferrara with Ercole II as maestro di cappella. He left there in 1558, and his last position was in Parma, where he died. The notes ignore the few months spent at St. Mark’s in 1562 as successor to Willaert.

These two Masses are built on French chansons, the closing work on one of his own, the opening one on a familiar chanson by Sandrin. If Rore’s own title sounds unfamiliar, the “black notes” are the short note values that dominated madrigal composition around mid-century. Its incipit is “Tout ce qu’on peut en elle voir.” Of his other three Masses, Missa Praeter rerum seriem has been recorded three times, most recently by Paul van Nevel (Fanfare 26:5), and Missa Vivat felix Hercules (8:3) was one of Alejandro Planchart’s last recordings. Of the three motets heard here, O altitudo was once recorded by Bruno Turner in a series of 10 Renaissance programs on Archiv and Fratres: Scitote was on an Eric van Nevel disc that never came this way, leaving Illuxit nunc and the two Masses as first recordings. While Illuxit nunc, a Christmas motet, is the shortest and slightest work on the program, the other two motets, both set to texts of St. Paul, are more exalted.

Stephen Rice’s splendid work

with his ensemble has been noted consistently in these pages. Most of his

work is narrowly focused on the mid-16th century, as is this disc. There are

13 voices for the most part, though O altitudo divitiarum, a text set by

more than a dozen of Rore’s contemporaries and a lyrical statement of the

wisdom of God, uses only 10. Fratres: Scitote, the narrative of the

institution of the Eucharist, is the only known setting of this text,

doubtless, as Rice says, because it was so central to the canon recited by

the celebrant that the choir had no opportunity to sing it, and Rore’s

setting was probably for extraliturgical use. The two Masses, like so many

of the type, display no trace of the secular origin of their cantus firmi,

moving simply and directly through the familiar texts. Here Rice’s ensemble

can demonstrate its lovely vocalism, balance, and response to its conductor.

As so often in unfamiliar Renaissance sacred music, we are left to wonder

how such beauties have been overlooked for centuries. In the times that saw

its own generation creating new forms and styles, there was no desire to

preserve what seemed so old-fashioned. We have the advantage of being able

to appreciate each style for its own best qualities. Rice is just one of

many who find more benefit in reviving the unfamiliar than duplicating the

well-known. If you know Rice’s previous discs, you will want to hear this.

If you have not, this is as good a place to start as any.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews