Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Jerry

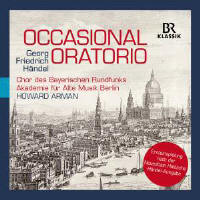

Dubins The title of Handel’s An Occasional Oratorio is best understood as “An Oratorio for an Occasion.” The question is what was the occasion for which Handel hastily cobbled together this choral work in 1745, borrowing bits and pieces from his other works, including the Music for the Royal Fireworks? The answer to that question reveals a streak of cynicism, or at least of opportunism, that led Handel to attempt to profit from a national emergency. Times were not good for the composer; both his finances and his health were strained, and he had repaired to Scarborough to recuperate and try to figure out what to do next. The English were done with Italian opera, which offended their national pride and sense of moral piety. The last in Handel’s long string of operas, Deidamia, had been produced in 1741. By then, he’d already seized upon the public’s taste for biblically-based English oratorios, and had successfully produced Esther, Deborah, Israel in Egypt, Saul, Messiah, and Samson. But in 1745, England was in crisis and the public was in no mood for more oratorios. The crisis, as documented in the booklet note and spelled out in even more detail in the album essay to the Hyperion recording of An Occasional Oratorio with Robert King and the King’s Consort, was the imminent invasion of England by Prince Charles Edward, the Young Pretender (aka Bonnie Prince Charlie), whose Jacobite army was marching south from Scotland to retake the throne from King George II. London was in panic mode, as the English army was recalled from Flanders to counter the insurrection. Handel saw this as an advantage to produce an oratorio that would rally the public’s spirits, inspire patriotic fervor, and make him a sort of national hero. At its first performance on February 14, 1746, at the Theatre-Royal in Covent Garden, however, the new oratorio was not met with enthusiasm by everyone, some expressing the same cynicism with which they believed Handel had approached the work. Charles Jennens, who had been Handel’s librettist for Messiah, wrote, “The Oratorio, as you call it, contrary to custom, raised no inclination in me to hear it. I am weary of nonsense and impertinence; & by the Account L[or]d Guernsey gives me of this Piece I am to expect nothing else. Tis a triumph for a Victory not yet gain’d, & if the Duke [of Cumberland] does not make hast[e], it may not be gain’d at the time of performance. ’Tis an inconceivable jumble of Milton & Spencer, a Chaos extracted from Order by the most absurd of all Blockheads, who like the Devil takes delight in defacing the Beauties of Creation. The difference is, that one does it from malice, the other from pure Stupidity.” There may be a note of professional jealously in the above, for Handel chose another librettist over Jennens to author the oratorio’s text, Newburgh Hamilton. The military victory was eventually gained when, under the leadership of the Duke of Cumberland, the English forces routed Bonnie Prince Charlie and his army at the decisive battle of Culloden. That’s the background of this rarely performed or recorded Handel oratorio, which certainly contains a goodly number of moving arias and stirring choruses. At first glance, it appears that this new BR Klassik version with Howard Arman may be cut because it contains a total of 44 tracks vs. 49 for Hyperion’s version with King. As it turns out, however, all but one of the differences in track numbers can be accounted for by Hyperion’s choosing to split the Overture, which is made up of four sections—Grave, Allegro, Adagio, and Marche—over four tracks to BR Klassik’s one. Right there, that accounts for four of the five discrepancies. The fifth I’ll come to shortly. To understand the performance choices each conductor has made, you need to know that Handel scored An Occasional Oratorio for only three vocal soloists: soprano, tenor, and bass. One of the numbers in Part Two of the work is a duet for soprano and tenor, “After long storms and tempests overblown.” Arman, in the new recording, performs it as written. But King, in his album note, states something that makes absolutely no sense. “Only three soloists, as we have seen, were named for the 1746 performances,” he writes, “but at least one other soloist must have been present, if only to sing the duet ‘After long storms…’.” What am I missing here? If you have three singers, and you only need two for a duet, why would you need a fourth? As just explained, Arman does nicely in the duet with soprano Julia Doyle and tenor Ben Johnson. But here’s where King pursues his “must have been another soloist” notion down the rabbit hole, telling us that in a later performance in 1747, “both Elisabetta de Gambarini and Caterina Galli took part as sopranos, a precedent we have used in this recording.” It’s not for the duet, however, that he calls upon his second soprano, Lisa Milne. Instead, he assigns the duet to lead soprano Susan Gritton and countertenor James Bowman, making it a duet for soprano and alto. Remember, though, that Handel included no part for an alto, male or female; thus Arman’s solution of assigning it to the soprano and tenor makes eminent sense. So what does King employ Lisa Milne for? Two solo arias, “Be wise, be wise at length,” and “How great and many perils do enfold.” Why King felt he needed to bring in a relief soprano for Gritton to sing these two arias, I have no idea. It only gets worse. King continues, “We have also allocated two low-set arias to an alto: otherwise the performing edition for this recording presents the movements heard in the 1746 performances.” The alto he’s referring to is once again countertenor James Bowman, who appears in the chorus with solo “May God, from whom all mercies” and the aria “Thou shalt bring them in.” But again, never mind that there was no alto in the original 1746 performance; so much for authenticity. Now, here’s the explanation for that one other difference, the fifth, in the number of tracks between the two recordings. For some unexplained reason, the aria, “Thou shalt bring them in”—the one King has arbitrarily assigned to a countertenor—is omitted altogether from the Arman recording. What David Ingram’s booklet note to the Arman performance does say is that “The present recording is based on the new edition of the Occasional Oratorio that was published in 2009 as part of the Halle Handel Edition. It takes into account for the first time all the important sources and variants of Handel’s oratorio score.” So maybe the aria “Thou shalt bring them in” wasn’t included in the original version. I’m afraid I don’t know. I note that Ralph Lucano chose the King recording for one of his 1995 Want List items in 19:2, but he seems to have done so mainly because it was the work’s first complete recording (until now, the only complete recording). I don’t believe it was ever reviewed, however. To be perfectly honest, I’ve never cared much for the King version, primarily because I’m not a fan of countertenors or of boy choristers in place of female sopranos, grievances I’ve expressed before; though certainly I have no complaints about Susan Gritton, tenor John Mark Ainsley, or bass Michael George, all of whom are highly experienced in music of the Baroque period and who sing with distinction. But as for the rest of it, until something better came along, King was the only game in town. Well, King and company can now be retired. Especially in light of what I now know about it vis-à-vis Arman’s new recording, there’s really no contest for which is the more HIP. Julia Doyle, Ben Johnson, and Peter Harvey are every bit the equal of their King counterparts; there is no alto, male or female, so that’s not an issue here; and the Chorus of the Bavarian Radio is a mixed group of adult men and women singers. The 32-member period instrument Academy for Ancient Music Berlin is sized and instrumented exactly the same as the King Consort, so I suspect that is what Handel called for.

Founded in 1982, the Berlin

Academy has had 35 years’ practice to iron out the kinks and cultivate a

well-balanced, well-blended, and tonally refined sound. Under the direction

of Howard Arman, this live performance, recorded in Munich’s Herkulessaal

der Residenz in September 2017 is really superb and makes a very strong case

for Handel’s neglected oratorio. Excellent booklet notes, full bilingual

(English and German) libretto text, and superb recording. Urgently

recommended. | |

|

Support us financially by purchasing this disc from eiher one of these suppliers. Un achat via l'un ou l'autre des fournisseurs proposés contribue à défrayer les coûts d'exploitation de ce site. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|