Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

International Record Review - (06//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Soli Deo Gloria

SDG719

Code-barres / Barcode : 0843183071920 (ID438)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

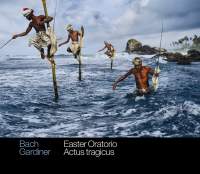

As so often in John Eliot Gardiner's Bach releases for Soli Deo Gloria, the cover photo

is spectacular, even if these Sri Lankan stilt fishermen seem to promise BWV88 instead of 106 and 249. Not much has changed in his overall approach for BWV106 since his 1989 recording ‑ understandably so, since that was one of the glories of his Bach recordings for DG. The instruments in the opening Sinfonia are slightly more individually present this time, the tempo again on the slow side but evocative and implacably sustained. The quick chorus 'In ihm leben und sind wir' is again impressively agile and clear. Peter Harvey is more defined in tone than was Stephen Varcoe ‑ in the 'Bestelle dein Haus!' section, although there is a slight touch of buffo at the very end of his solo which does not completely convince. (The comparison with Stephan Schreckenberger's entirely convincing easy gruffness for Cantus Cölln is enlightening ‑ Schreckenberger's complete case with the language helps him inhabit the interpretation to an extent that probably only a native German speaker could muster.) The fugue 'Esist der alte Bund' seems to stretch the new Monteverdi Choir a little more than it did its predecessors: the basses are a little too vibrant to blend completely and their lowest notes in the first entry drop out of the picture.

Gardiner's solo team here do not quite reach the heights that Nancy Argenta, Michael

Chance, Anthony Rolfe Johnson and Varcoe managed a quarter of a century ago. The new quartet is a little undifferentiated, the mezzo and baritone sounding rather close in colour to their higher neighbours. The soprano solo singing on alone while the entire vocal and instrumental texture evaporates around her is one of the finest dramatic touches in Bach's entire output. Argenta was truly splendid in 989 but in comparison Hannah Morrison sounds a touch too knowing, not least in her final ornament. It is hard not to feel that performance practice might have overtaken Gardiner's view of the work in the past decades. The revelations brought by such groups as Cantus Cölln and the Ricercar Consort, with an intimate chamber approach and a closer relationship with the language bringing an enormous palette of detail, are impossible to unhear, which in no way invalidates Gardiner's 1989 recording but makes the 2013 remake seem a slight anachronism.

In his booklet note

Gardiner admits to puzzlement as to 'why the Easter Oratorio is

sometimes considered the ugly (or at least forgotten) duckling among Bach's

choral works' ‑ he then answers his own question, referring to the work's

parody original, with the four shepherds of the original transformed

'not wholly convincingly' into Christ's disciples. This is

certainly a grand version of Bach's relatively modest Resurrection drama

in which Jesus makes no appearance: Bach himself gave the cue with

a full orchestration including three trumpets and two oboes and Gardiner in

response has swelled the English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir to

full Handelian glory, with 11 violins and a choir of 8.5.5.5. The Sinfonia

is resplendent in these colours, not only in the clatter of the trumpets but

in the long Adagio oboe solo, given with superb control here by

Michael Niesemann. The chorus 'Kommt, eilet und laufet' is taken at a

breathless pace. 'Come, hasten and run', says the text, although slightly

slower versions do reveal other dimensions to the music: the Bach Collegium

Japan rendering, with a 'mere' 16 singers and 6 violins, has rather more

spring in its step.

Of course there is no question of Gardiner adopting an even

remotely sceptical attitude to Bach's music but his interpretative choices

do not always work in the oratorio's favour. Although the performers are all

on fine form the flanking choruses here seem overblown and the intimate

arias overshadowed. Gardiner would certainly not agree with Andrew Parrott

or Sigiswald Kuijken that Bach might have used just 4 singers instead of 23

but those chamber versions avoid any suspicion of grandiosity while

capturing an intimate simplicity that has no place on Gardiner's palette but

casts a far more endearing light on Bach's ugly duckling.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews