Reviewer: Peter

Loewen

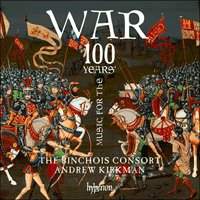

As usual, the Binchois Consort

has brought together a beautiful program of early-Renaissance masterpieces.

After singing the introduction ‘Anglia Tibi Turbidas’, they perform works by

Johannes Alanus, John Dunstaple, Leonel Power, Forest, and others to tell a

story of how English composers responded to the struggles of war in the

early 15th Century and took comfort in their national pride, the support of

protector saints, and by reveling in their victories.

The program is divided into four narrative sections titled

‘Kingship and the Rise of Nation’, ‘St Thomas Becket—Protector of England’,

‘St Edmund, King and Martyr—Protector of England,and ‘ ’ The Coronation of

Henry VI’. Except for ‘Ecce Mitto Angelum’ and ‘Pastor Cesus in Gregis Medio’,

which are chants, the program consists of polyphonic music - Dustaple’s Da

Gaudiorum Premia Mass, the famous English ‘Agincourt Carol’, and several

Latin motets. The motets are especially compelling in this context, as they

are narrative pieces by nature. Like the frames of a stained glass window,

each line of a motet offers a self-contained story. But as with windows,

whose larger message becomes clear as the panels are simultaneously

illumined by the sun’s light, so the lines of a motet reveal a deeper

narrative meaning when they are heard simultaneously through the art of

music; the challenge, of course, is to hear as clearly as one can see.

Alanus’s ‘Sub Arturo Plebs/Fons Citharizancium/In Omnem Terram’ (so titled

because each vocal part bears a different text) is an outstanding example of

the narrative properties of motets. The tenor line, a setting of Psalm 19,

announces the power of “their voices” that sing to the ends of the earth,

while the upper (triplum) voice identifies those “voices” with several

famous English composers and music theorists. The middle (duplum) voice, at

the same time, establishes the legacy of great composers—from Tubal to

Pythagoras, Gregory the Great, Guido of Arezzo, and Franco of Cologne—as

though it were instantiating the authority on which English greatness rests.

And to show his listener that Alanus saw himself as part of that legacy, he

demurely adds his name (“J Alanus minimus”) as an inheritor of this

authority. Interlocking patterns of repeated melodies and rhythms help to

organize textual and musical phrases in these motets. In fact, Dunstaple’s

motets are often pan-isorhythmic—a real contrapuntal tour de force when one

considers the difficulty of coordinating different repeating rhythmic and

melodic patterns in each vocal part. In ‘Veni Sancte Spiritus/Veni Creator

Spiritus’ Dunstable uses repeating melodies and rhythms to coordinate two

well known chants; but he also adds complication when he submits the lower

two voices to a three-fold program of diminution, so that by the time they

reach the final section of the motet, the duration of their pitches is one

third the length of the ones that sang at the outset.

The music itself, then, has its own rhetorical register, which

brings out incrementally the excitement inherent in the text. The Binchois

Consort has a knack for this repertory. Their intonation and balance are

spot on, and the ease of their singing seems to belie the technical

difficulty of the music. Texts and notes are in English.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

|