Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

Brenesal

The year 1685 was very

musically productive for Lully. In other respects, however, it provided the

rare spectacle of the usually sure-footed, ambitious schemer publicly caught

in several problems of his own making. These began with a prominent scandal

involving a young musical page of the King. Louis XIV, who took a poor view

of the blatantly promiscuous and bisexual affairs of his superintendent of

the Royal Opera, finally had enough, and let it be known that he was

withdrawing his protection from the composer—a very important loss, since

Lully was a selfish and ruthless monopolist who had made many enemies over

the years. Lully then proceeded to cancel pensions for several of the older,

retired performers at the Opera, which led to four of his star singers

leaving in protest. Again, Louis XIV intervened, and cancelled Lully’s

express order. (Louis hated spending time micromanaging his top people, and

saw their embarrassments as reflecting upon him.) Later in the year the

Theatine monastery near the Louvre began selling tickets to public concerts

of Roman oratorios, which Lully saw as a challenge to his legal authority

over French opera. Louis disagreed once more, and refused to shut them down.

The gulf further widened between king and subject when Lully, who was

severely ill at the same time as Louis, tried to influence his sovereign’s

behavior favorably by drawing attention to the heavy workload he continued

cheerfully to bear. As Nancy Mitford noted in her book on The Sun King,

Louis XIV only rarely had sympathy with another’s physical failings, and was

usually disgusted by what he saw as attempts to play on his emotions. The

composer must have been desperate to try this ploy, and in any event it

didn’t work.

Armide appeared at this

point. It was initially meant for performance at Versailles, but ran afoul

of the continuing success there of another of Lully’s works, Le Temple de

la paix, which pushed back the schedule. It was finally given at Lully’s

own Théâtre Royal de Musique in Paris, starting in February 1686, and—no

doubt to the great relief of both composer and librettist—immediately proved

one of their greatest triumphs. It was to be the last tragédie en musique

completed by the composer, who died the following year.

In France at the time, an

opera’s libretto was considered of equal or greater value to its music, so

that a poor text could sink an otherwise meritorious work. Quinault was,

fortunately for Lully, a remarkable librettist, equal to the best of any

age—and in the central figure of Armide he created a complex, heavily

flawed, but ultimately sympathetic character. All others in the opera are

secondary to her, but none of them are without their own deft, dramatic

touches, from Renaud’s empathy and moving generosity of spirit in act V, to

Ubalde’s flaw revealed in act IV, and derived from regret for a long lost

love. Lully responds with music that carefully follows the expressive

concerns of his collaborator—whether it be the warm lyricism and sprightly

dances of the prologue, the beneficent chorus, “Ah! quelle erreur,” the

various airs of dialogue between Armide and Hate (La Haine), or the grimly

magnificent Passacaille of act V, with its variations that include Renaud

and the chorus.

So popular did Armide become

that one of its monologues of accompanied recitative, the heroine’s Enfin

il est ma puissance, came to be regarded by both the French musical

establishment and many Lullyistes as the best of its kind, an example of how

such things should be done. Within this context it’s worth noting the

conclusion of a lengthy letter published in 1753 by Jean-Jacques Rousseau,

who loathed French opera, and whose attempt at analysis of the monologue

eventually devolved into this: “I think I have shown that there is neither

measure nor melody in French music, because the language is not susceptible

of it; that French song is nothing but a continual barking, insupportable to

every ear that is not prejudiced; that its harmony is crude, without

expression, and feelings only fit for a schoolboy; that the French airs are

not airs; that the French recitative is not a recitative. Whence I conclude

that the French have no music and can not; or that if they ever have one, it

will be so much the worse for them.” As frothing-at-the-mouth rants go, it

is wonderfully formidable. Armide has been blessed among Lully’s operas with several distinguished recordings. An 1983 abbreviated concert revival featuring Rachel Yakar and led by Philippe Herreweghe turned into a recording (deleted; Fanfare 7:5) that is disciplined, stylish, and reasonably well sung, though the conductor later took it to task. A second, more complete recording under his baton appeared in 1993, and is now available either used or as a download. Howard Crook’s Renaud is musical if somewhat colorless, but Guillemette Laurens as Armide is as vividly memorable as one could wish, and the finest on record.

Unfortunately, Ryan Brown’s

recording with his Opera Lafayette (Naxos 8.660209; Fanfare 32:5) is

damagingly cut. The two most serious excisions are the removal of the

musically attractive prolog, and the elimination of act IV, scene 4:

psychologically perceptive, as usual with Quinault, and Lully in his best

second manner, haunting and sensuous. It’s all the more regrettable in that

while Stephanie Houtzeel as Armide enunciates poorly and possesses the wrong

vocal weight for the role, Robert Getchell is the best Renaud on records. (There is also a recording of extended excerpts from acts II and V made in 1972, featuring Jean-François Paillard’s direction, Nadine Sautereau, André Mallabrera, and Roger Soyer. It was released in the US as MHS 867, and is worth getting for Sautereau’s combination of bright, diamond-focused tone and typically French elegance.)

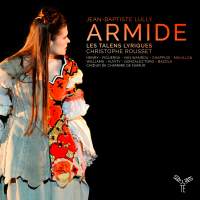

Christophe Rousset also has a

problematic Armide and an excellent Renaud. Marie-Adeline Henry, an artist

I’ve admired for some years for her intelligence, tonal variety, and

insight, may have been going through a bad patch when she made this

recording. She has breath support issues in the famous act II monologue

mentioned above, breaking up Lully’s long line and audibly gasping at times.

Figured passages are regularly slurred, pitches go awry in the contrapuntal

chasse “Poursuivons jusqu’au trépas,” and she swoops continuously in an

unpleasant fashion. Antonio Figueroa, however, is excellent. His voice is a

shade less settled than Getchell, but just as attractive for its silken

tone—“Les Plaisirs ont choísí pour asile” in the Passacaille is as fine as

one could wish, this side of the ghost of David Devriès—and elsewhere

catches the martial side of Renaud’s character better than any other

performance I’ve heard. In fact, Rousset has an embarrassment of riches in four excellent tenors. Besides Figueroa, there’s Cyril Auvity, whose disc of airs de cour (Glossa 923601) was on my 2016 Want List, and Marc Mauillon, the excellent Adonis in a recording of Blow’s Venus and Adonis (Alpha 703) that made my 2014 Want List. (The thankless part of Artémidore is graced by Emiliano Gonzalez Toro, whom I praised for his performance as Hyllus in Dauvergne’s Hercule mourant.) Both are in fine voice here, though neither gets much opportunity to show off his virtuosic agility. Douglas Williams is an imposing Hidraot. In the various important but tertiary roles that are gathered up here into two bundles, Judith van Wanroij is distinguished for her even vocal production, fine phrasing, and warmth of tone. Marie-Claude Chappuis suffers by comparison from an unequalized voice, with the shift between registers glaringly obvious. She is an intelligent singer, however, and enunciates well.

Rousset uses a judicious mix

of tempos, remaining ever alert to instances of orchestral color and

rhythmic variety. His version of the delightfully pastoral “Plus j’observe

ces lieux” is probably more authentic in its pacing at roughly 142 bpm than

Brown’s, but I confess that the latter’s 116 bpm, strongly abetted by

Getchell’s breath control and perfect emission, casts a memorable spell.

Elsewhere, though, I would give the palm to Rousset, who has the superior

ensemble in both Les Talens Lyriques and the Chœur de Chambre de Namur, both

completely responsive to his stylistically informed wishes.

If Henry’s eponymous heroine

was the equal of everyone else in the cast, a strong recommendation would be

a given. However, her performance is adequate at best, and very mannered at

worst. If you don’t mind downloads, it’s worth listening to Herreweghe’s

second recording to see if it will suffice. Otherwise, this performance is

very tempting, despite being an Armide effectively without an Armide.

| |

|

Support us financially by purchasing this disc from eiher one of these suppliers. Un achat via l'un ou l'autre des fournisseurs proposés contribue à défrayer les coûts d'exploitation de ce site. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|