Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

Reviewer:

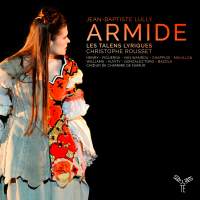

David Vickers

High tenor Antonio Figueroa sings Renaud idiomatically and sweetly in the pastoral sleep scene that forms the bulk of Act 2 (‘Plus j’observe ces lieux, et plus je les admire’); this ranks among Lully’s most beautiful creations and has even greater compositional finesse and flexibility of form than the sommeil in Atys. The blissfulness of demons disguised as nymphs and shepherds laying enchanted garlands of flowers on the sleeping hero is disturbed by the violent transition into the titular sorceress’s anguished monologue ‘Enfin il est en ma puissance’, in which she cannot bring herself to stab to death the slumbering Renaud: Marie-Adeline Henry captures the full measure of Armide’s conflicting emotions, and the undercurrent of theatrical tensions produced by Rousset and his band indicates why Rameau judged this sensational music to be worthy of analytical praise in his 1754 Observations. Unremitting tension continues in Act 3: Armide’s guilt that Renaud’s love is illusory causes her to invoke Hatred (sung menacingly by Marc Mauillon), only to change her mind at the climax of an extraordinary ombra divertisse-ment in which Hatred, male chorus and dancers attempt to break Cupid’s bows and arrows. The respite provided by the lighter tone and entertaining magical mischief of Act 4 is judged charmingly as two Christian knights fend off seductive demons in order to come to Renaud’s rescue (there is especially fine singing from Cyril Auvity’s Danish Knight and Marie-Claude Chappuis as a demon impersonating his beloved Lucinde). The long passacaille for the Pleasures and ‘a band of fortunate lovers’ (Act 5) must have inspired the corresponding passacaglia in Purcell’s King Arthur a few years later; its sensually shaded performance by Auvity, the Namur Chamber Choir and Les Talens Lyiques demonstrates Lully’s art at its most appealing. |

|