Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Dan

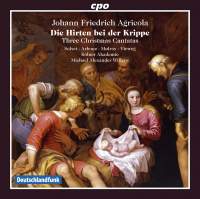

Sperrin Johann Friedrich Agricola (1720–1774) was Bach’s student. At one time, amazingly, he was also his son-in-law. When we listen to these Christmas cantatas, it is evident everywhere: He has Bach’s endless sense of undulation, his deeply archaic quintessence, and the flavor of theological fervor that never tips into camp reverie. If you put this on in the house, it will be a thoughtful Christmas indeed. Feeling Christmassy through music is a strange and occasionally stupid enterprise. The inane kitsch of the 20th century swallowed up Baroque classics, of course, and turned them into “cultural” CDs given to grandparents, something to have on in the background. The essential spirit of Christmas, in this way, feels like a Handelian phenomenon as much as a Dickensian one: that sense of the domestic spirit, the happiness in generosity that is occasionally put-on during the most mirthful, gout-ridden time of year. Agricola reminds us, in the occasionally dark spirit of the cantatas, that Christmas is actually a time of plangent thought, of an understated rejoicing that for many Christians, in Agricola’s time as much as ours, is at the center of their faith. There is definitely a tinselly shimmer to the grander moments, and as you work through the first cantata you can see snow and hear bells. However, the fifth track of the CD opens with a darker arpeggio flurry on the lower strings; it is a brooding and patently secular moment of arresting intensity, and it cuts through the righteous happiness of the opening. These moments, usually on the continuo and lower registers of the strings, give a pleasingly varied texture to a work that openly drones on the same string of rejoicing. This nuanced, complex conception of the season, which feels so Bachian, is refreshingly set against our commercialized Christmas. Direct allusions to Bach are lurking everywhere, but perhaps one example will suffice to illustrate how pleasing an inheritance it is. The seventh track, “Uns ist ein Kind geboren,” is a curious piece of monody (which itself is a fittingly domestic form of recitative) with male voice and miniature organ. It is a stunning patchwork of harmonic suspensions and melodic wavering, which is worrying about itself and tortured over the text. For me, it has a direct parallel in Bach’s Cantata 146, the recitativo, which of course speaks in a language common to all writing of monody, but seems to carry the same suspensions at the same tactical moments to heighten the tension over the text and put the voice and organ in rhythmic conflict. This is one of many places where copying Bach’s music as a student seems to have filtered in Agricola’s style. All else is treasure: tweets of recorder, miniature trumpet voluntaries, and a perfect reciprocal relationship between vocals and instruments. It is worth comparing with the Naxos recording of Agricola’s Fortuna Desperata (Unicorn Ensemble, 1999), which has a muddy acoustic but a pleasingly plangent tone, and with Bach’s Christmas Oratorio just to compare how Christmas is figured differently in Agricola’s overt “Berlin” style. It is occasionally fun to hear how the Leipzig (Bach) style blends with the modern, exciting, and cosmopolitan energies of fashionable Berlin, especially for a space as grand as St. Peter’s Church, in which it was first performed. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|