Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

International Record Review - (02//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

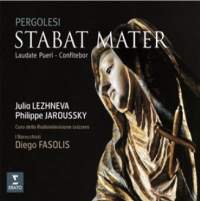

Erato

3191472

Code-barres / Barcode : 5099931914727 (ID380)

It is quite likely that Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater

was the single most reprinted, republished,

copied, performed and arranged composition of the eighteenth century. It was

originally written as a replacement for a setting by Alessandro Scarlatti

and used the same scoring of a soprano and a mezzo or alto with a small

string ensemble. The fact that it was the last work written by Pergolesi,

who died aged 26, added considerably to its mystique and popularity.

However, even at the time some critics, such as the learned Padre Martini,

thought it too operatic and lightweight in mood for its weighty subject

(Christ’s grieving mother standing at the foot of the cross). Nonetheless,

until the very end of the century most admired its proto-galant style

superimposed on a basically Corellian musical language. Even J. S. Bach was

not immune to its Italianate appeal, using it as the basis for his setting

of Psalm 51 (in respectable German, of course!).

Leaving aside the many fake Pergolesi compositions surviving — including the pieces Stravinsky used in Pulcinella — his only other really well-known work is the little comic opera La serva padrona, of which, just occasionally the Stabat mater is disconcertingly reminiscent . Recently, the continuing popularity of these two works has led musicians and record labels to explore both his opera seria and sacred repertory, uncovering many works of outstanding quality. Among them is Pergolesi’s setting of the Psalms Laudate pueri and Confitebor for two high voices, choir and orchestra. The Laudate pueri appears on both the present recording and the comparison disc on Oehms Classics.

The Stabat mater appears often on disc and in concert, usually in the original version without choir. The second comparison recording on Tudor performs some movements using a boys’ choir (a very good Swiss one). This it justifies in the booklet essay with some vague talk of offering ‘an update of the debate about historic performance practice’, but, as the work was performed all over Europe for decades after Pergolesi’s death, no doubt adapted to local tastes and conditions, one cannot be too dogmatic on the subject. Of the many recordings that simply use a soprano and a mezzo or alto, many performed it with big female voices more suited to a nineteenth-century opera house than the small Neapolitan chapel for which it was written. A small number use a boy soprano and a countertenor, including the famous version Harmonia Mundi sung by Sebastian Hennig and Rehé Jacobs, and the highly recommended new recording on Tudor, which features Jonah Schenkel, an exceptionally mature-sounding boy singer, and the fine English countertenor Alex Potter… Some recordings paired a gifted and stylistically aware soprano (for example, Mária Zádori or Susanne Rydén) with a much less-satisfactory countertenor. Only a few, such as the now venerable L’Oiseau-Lyre recording with Emma Kirkby and James Bowman, seemed to have got everything right. The Oehms recording is really in a class of its own in several respects. I know of no other account with two adult male voices, nor one that takes such exuberant liberties in phrasing and ornamentation. The soprano line is taken by the falsettist Valer Barna-Sabadus, who is a very exciting singer, but whose voice is certainly an acquired taste.

The new recording by Julia Lezhneva and Philippe Jaroussky, conducted by Diego Fasolis, is positively sober by comparison; but what it lacks in surprise it more than makes up in musicality and vocal purity. The conductor on the Oehms recording, Michael Hofstetter, consciously set out to strip the Stabat mater of cloying sentimentality and the results are startling. Fasolis takes a different route: sheer vocal beauty and intensity of expression. The result is staggeringly beautiful and surprisingly profound. Padre Martini’s concern that Pergolesi’s music is too frivolous for its subject matter is understandable; but this performance proves that, rightly performed, it has a lot more than surface charm.

I worry that Jaroussky is sometimes mixing with the wrong crowd (stylistically speaking, of course). So pairing him with the ultra pure-voiced Lezhneva is an encouraging collaboration. I suspect she also benefits from his longer immersion in late-Baroque vocal style. When they sing together, their voices blend seamlessly — something almost impossible when constant vibrato is present. Fasolis makes use of moderate tempos to shape each movement exquisitely. The result is quite the finest Stabat mater on disc.

In the delightfully festive Laudate pueri, Barna-Sabadus, while impressive, is no match for Lezhneva in the fond soprano part. Terry Wey is a closer competitor for Jaroussky. Both I Barocchisti (Erato) and the Neumeyer Consort (Oehms) play the rich score with skill and flair. Where Fasolis scores the knock-out, though, is his choir: the highly disciplined Coro della Radiotelevisione svizzera, next to which Hofstetter’s Ensemble Barock Vocal from Mainz sounds quite scrappy.

Sparkling recorded sound from Erato, a lucid and

comprehensive booklet essay from IRR’s Simon Heighes and, above all of

course, simply ravishing music-making, add up to an unquestionably

outstanding release.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews