Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

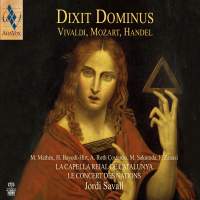

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

Psalm 110 (or according to

some translations, Psalm 109), the Dixit Dominus has been a favorite of

composers. As an overall text, it covers a wide variety of moods and

imagery, and within itself contains subdivisions, such as the Tecum

principium, that offer opportunities for separate smaller sacred works.

Almost every composer of the late Baroque and Classical periods set either

the complete text or portions. Here one has a performance of three of the

major figures, beginning with Vivaldi’s large multi-movement work (RV 595)

from 1717. It was presumably written for one of the larger churches in

Venice, since his day job at the Ospedale della Pietà would normally have

meant women’s voices only (though they could have easily adapted the

four-part chorus and bass solo parts). The use of a pair of trumpets allows

for the opening homophonic chorus to be quite festive, followed by the Donec

ponam with its restless dotted string accompaniment. Vivaldian rhythmic

structures also support the several solo arias, beginning with the jaunty

Virgam virtutis, where the virtue apparently lies in the perky and quite

florid soprano part. The Tecum principium duet for duo sopranos accompanied

by lower strings is rich from a textural standpoint, with the higher pitched

voices (reminiscent of the Laudamus te from the famed Gloria) providing a

registral contrast. The aria Dominus a dextris tuis begins with some solo

trumpet fanfares with the same march-like dotted rhythms, before the voice

and trumpet engage in a question-answer that expands into a fluid coloratura

line. With the words describing the Day of Wrath, the chorus enters

accompanied by some furious string tremolos; Vivaldi uses them in unison

with considerable effect. In the De torrente there is a hint of the tone

painting used in the softer parts of the Seasons, where the flowing of the

brook is represented by long melismas above an insistent ostinato. At the

end, of course, is the doxology, here in three parts, a trio and two

choruses. The last is a fugue that really seems more like canonic imitation

than a real bit of complex counterpoint, and in the end the musical edifice

congeals into a homophonic close.

The Vivaldi Dixit makes a nice

contrast with the other main feature of the disc, Handel’s large-scale

setting (HWV 232) composed early in his career in 1707, a decade before

Vivaldi. The opening chorus, with its odd interpolations in the minor key at

emphatic points, is like a perpetual motion machine, with the running

strings cycling through sequences without cease. The cries of “Dixit” are

like pointed announcements, though there is a nice set of suspensions that

thicken the texture in almost cantus firmus fashion. The Virgo virtutis is a

nice continuo aria of the sort that hints at Alessandro Scarlatti, with the

bass line walking in a steady pace matched by the alto. In the chorus

Juravit Dominus the solemn introductory chords of each short section unravel

into a more contrapuntal choral section that is reminiscent of Handel’s

famed oratorio writing. This is followed by a rather gnarly fugue, and the

Dominus a dextris in turn becomes a Corellian movement, with a running bass

above which the voices soar with broad suspensions. One can hear the

marching of an implacable army in the pointed lines of the Conquassabit

capita, while in the De torrente a slowly unfolding string ostinato with

some rather close harmonies and vocal suspensions paints a picture of

mystery rather than a flowing river. It is more like the current of

something broad and calm rather than swift and turgid. Handel’s fugal close

is more complex than Vivaldi’s. Both of these composers were to set the same text no fewer than three times, but each of those settings is too long to pair with these first examples. Besides, if one was chosen, the idea of musical contrast would tend to favor one or the other. Therefore, Jordi Savall chose a shorter companion to separate the two performances, Mozart’s early Dixit et Magnificat (K 193). This is set for a festive orchestra of strings and trumpets for Salzburg in 1774. Normally, he would have included this a part of a Vesper setting, in which it does belong generally as a single movement, and it is not beyond the realm of possibility that that was precisely what he intended, especially since he also paired it with the final movement of the Vespers, the Magnificat. The possibility that the other movements such as the Laudate pueri are missing cannot be dismissed, but the surviving pair represents his normal church style of this early period. The choral portions are neatly homophonic for the most part, with the occasional excursion into a bit of counterpoint. The Et in saecula saeculorum fugue is especially well done, though brief. All of these pieces have been recorded before, so comparisons abound. But the program chosen by Savall works as a trilogy of pieces. Soprano Hanna Bayodi-Hirt is light, perhaps a bit too light in places where she sounds a bit thin, but her counterpart Marta Mathéu is more robust, and Anthony Constanzo has a nicely resonant countertenor. Makoto Sakurada is flexible in his renditions; bass Furio Zanasi blends well, especially in the trio Gloria Patri of the Vivaldi. I like Savall’s tempos, which move the works along but are sensitive to the often complex lines. As one might expect, the Concert des Nations is precisely in tune, and the chorus from Catalonia is as disciplined as a smoothly functioning machine. They are clear and precise, never muddy, so that the articulation of the text is never obscured. All in all, this is a fine disc and is recommended. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|