Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Trčs approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Andrew

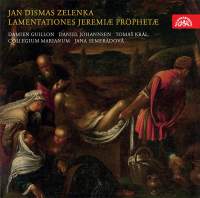

O'Connor Since the early 1980s it has seemed that no recording of Zelenka's Lamentations ofJeremiah ‑the Prophet, ZWV53, could equal, let alone surpass, the version featuring artists from the staff of the famed Early Music academy Schola Cantorum Basiliensis (SCB). Even by Zelenka's standards, this set of Holy Week lamentations, composed in 1722 for the Catholic Royal Chapel in Dresden, is a work of the highest genius and greatest depth. The background is well explained in a typically informative essay by Zelenka scholar Vaclav Kapsa. The Lamentations requires three solo singers ‑ alto, tenor and bass ‑without a choir, plus strings and solo oboes, flutes, cellos, chalurneau and bassoon. The pairs of oboes appear in all the Lamentations for Holy Wednesday and Maundy Thursday, giving a dark quality to the harrowing texts. The other solo instruments are reserved to give a distinctively lighter hue to the Good Friday, foreshadowing the forthcoming resurrection and redemption. Each lamentation is sung by a single voice. On the SCB recording, these were René Jacobs, back when he was still an active countertenor, the famed Early Music tenor Guy de Mey and the bass Kurt Widmer, whose luminous voice also had a slightly lugubrious quality particularly well suited to lamentations. Jacobs also directed the performances. They and their instrumental colleagues seemed really to inhabit this unsettling and profound music. Subsequent recordings on Hyperion (Michael Chance, John Mark Ainsley, Michael George) and Globe (Ulla Groenewald, Hein Meens, Max van Egmond), though not without merit, fell considerably short of the SCB's recording. If a new version were ever to challenge the SCB classic for supremacy, it was also likely to come from Supraphon. Bohemian‑born Zelenka has no greater modern champion tham the Czech label, which boasts three or four world‑class period‑instrument ensembles on its roster, all of which have devoted recordings to his music. I recently attended several outstanding concerts of Zelenka and contemporaries by Collegium Marianum, led by the Baroque flautist Jana Semerádová, as it was one of the major performers at the 2014 Utrecht Early Music Festival. Even by the high standards of ensembles at that festival, Collegium Marianum stood out for its fresh, thoughtful and exuberant music‑making. Semerádová shapes every phrase with care and precision, while directing her musicians with the poise an grace of a ballerina. Interestingly, one of Collegium Marianum's violinists is her husband Vojtěch Semerád, who also possesses a fine tenor voice and led another ensemble in Utrecht in a concert of Renaissance polyphony. On hearing of the forthcoming recording of the Zelenka Lamentations, I was disappointed to see that Mr Semerád was not singing the tenor part. Unfamiliar with the Austrian tenor Daniel Johannsen (who does not on paper share Semerád's Early Music credentials), I was prepared to be disappointed. On his first appearance in Lamentation I for Maundy Wednesday, all seemed well. Johannsen's light, agile voice seemed fresh and clean, with a well‑controlled vibrato and the excellent breath control demanded by Zelenka's often long‑spun lines ‑ even if he did not quite match the easy elegance of de Mey at his youthful best. (Then again, which singer ever has?) But things go very wrong when Johannsen returns to sing the first of the Good Friday lamentations. So inferior is the singing ‑ tentative, insecure in pitch and afflicted by a nervy vibrato ‑ that I rechecked the booklet to confirm that it was indeed the same singer. Unless Johannsen suffered some malaise in the middle of the recording, it must be a deliberate choice to sing the two lamentations so differently. How very odd ‑ and seriously misguided. The two other singers are more established Early Music stars than Johannsen, The. French countertenor Damien Guillon is a highly sought‑after singer of Bach cantatas. The young bass Tomá Král appears with all the Czech Baroque ensembles and increasingly with groups from all over Europe. Both sing superbly throughout the disc. Each performs two lamentations and, in a bonus over the SCB disc, they also sing three Gregorian chants from Holy Week ceremonies to supplement Zelenka's settings. Guillon's singing is both pure in tone and highly expressive. Král is just about the best Early Music bass around at the moment: sometimes billed as a baritone, his voice is dark, lithe and agile ‑ without a hint of the bluster basses can fall into. Playing Zelenka's rich and inventive instrumental score, the SCB recording boasted some of the leading period‑instrument exponents of the day, such as violinist Jaap Schroeder and oboist Renate Hildebrand. It is a sign of the progress of the Early Music movement that Collegium Marianum's instrumentalists are superior in every case. The Supraphon recording also gives the instruments more prominence than the older recording, which unduly favoured the singers. But for Johannsen's bizarrely sub‑par performance in one of his two appearances, this otherwise first‑class recording would finally have edged aside the 1982 SCB performances as the finest on disc. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|