Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 37:3 (01-02/2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

Naxos

NAX8572866

Code-barres / Barcode : 0747313286676

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

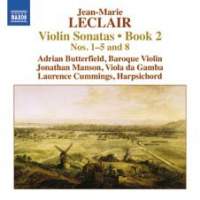

Several years ago, the three Naxos discs comprising Adrian Butterfield’s performances of Jean-Marie Leclair’s first book of violin sonatas (Naxos 8.570888, 8.570889, and 8.570890) appeared, and I highly recommended them in Fanfare 35:3. Butterfield and harpsichordist Laurence Cummings have now returned, with Jonathan Manson rather than Alison McGillivray playing the viola da gamba, with an installment of six sonatas from the composer’s second book. Butterfield’s own notes relate that this set includes five sonatas for violin or flute (two occurred in the first book); and Butterfield emphasizes that Leclair intended these works for a wider group of performers.

The program, in order, opens with one of the sonatas in which Leclair offered the choice of violin or flute. Its four movements begin with an arch Adagio in which Manson displays the richness of the seven-string gamba made in 1978 by Curtis Bryant (Butterfield plays a violin made by David Rubio in 1996 after the 1734 Rode Guarneri del Gesù, while Cummings plays a 2000 harpsichord by Andrew Garlick based on a 1748 model). The book of sonatas appeared in 1728, after, according to Butterfield, Leclair had studied for a time in Turin with Corelli’s student, Giovanni Battista Somis. William S. Newman suggests that, through Somis, Leclair made the acquaintance of the music of both Corelli and Vivaldi; and later he would come under the spell of Corelli’s student Pietro Locatelli, whose devilish virtuosity appears, though restricted mainly to the lower positions, in Leclair’s later books of sonatas. Butterfield draws comparisons between Leclair’s allegros and Corelli’s, but Somis’s sonatas, at least the later ones of op. 4 (written in 1726, about the year Leclair visited him), fall into three rather than four movements, as all these do. Somis’s works also don’t push the technical envelope far beyond Corelli’s—they’re very tame, as these by Leclair, for the most part, prove to be. Nevertheless, the Second Sonata in Leclair’s set employs double stops freely, and represents generally a more advanced technique. But Butterfield and his ensemble find the commonalties in these works, whatever their instrumentation or technical demands, in the starchy French style in which they present what Leclair had absorbed of the Italian style from his travels. And in the Finale of that Second Sonata, they abandon themselves to an Italian energy that recalls Vivaldi’s, featuring cadenza-like passagework.

The Third Sonata returns to the instrumental choice offered by the First Sonata—violin or flute—and therefore to the more moderate technical demands such a choice implies. Butterfield points out in the notes the melodic affinities of the opening movement of the Fourth Sonata to Corelli’s style, a parallel he and the ensemble exuberantly draw in the performance itself. But those familiar with Somis’s sonatas may find that these works resemble his as closely as they do Corelli’s. In any case, the ensemble brings sonorous virtuosity to the third movement, a double-stopped “Aria: Gratioso.” The Finale combines Corelli’s melodic manner with technically more demanding swirling double stops.

The Fifth Sonata again suggests the simplicity of an arrangement for violin or flute, but its first movement offers Manson, again, an opportunity to display the richness of both his tone and his musical imagination. After a Corellian (or Somisian) Allegro of considerable melodic and rhythmic verve—at least in this performance—the Sonata proceeds through an elegant Gavotte to a piquant Finale, in which Butterfield’s tart ornamentation lends a brisk energy. Butterfield points out that Leclair conceived the Eighth Sonata as a sort of duet for violin and gamba, and his interaction with Manson in the first movement bears out this observation. Its imitative second movement takes advantage of the same manner of writing, even if it isn’t so thorough-goingly polyphonic as similar passages in Corelli’s church sonatas. But Corelli’s personality shines through this movement’s melodic contours as well as through its counterpoint. The Sarabanda offers particularly rich opportunities for conversation between the violin and gamba; the Finale contains chains of trills that enliven its melodic discourse.

Butterfield remarks that violinists have not taken up Leclair’s first two books of sonatas, perhaps because of their modest demands; perhaps his insightful and cleanly-recorded performances (along with those of the first book) will revive some interest in them. Strongly recommended—and not just for the violinistic moments.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews