Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Brian

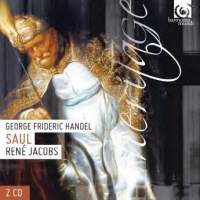

Robins As things stand up to this point, the situation regarding recordings of Saul is unusually clear-cut. Reviewing the Paul McCreesh Archiv version of Handel's immense music drama in Fanfare 28:1, both my colleague Bernard Jacobson and I concluded it was hors concours, although for me there are still aspects of the older Eliot Gardiner Philips set that were not excelled. My own verdict summed up McCreesh's interpretation as being one of “blazing, searing conviction,“ and it duly appeared in my Want List for 2004, as indeed it did in Jacobson' s.

I went into the background of Handel's revolutionary epic in some detail in the course of the McCreesh review, so will here content myself with a précis. At the heart of Charles Jennens's skillfully constructed libretto lies the story of the self-destruction of a powerful hero, King Saul, a theme handled by both Jennens and Handel with extraordinary sensitivity and sympathy. Although his music is largely restricted to some of Handel's most dramatic accompanied recitatives, Saul is the pivot around whom all the other characters orbit, his huge presence constantly dominating the action. Only at the very last is the mourning for the dead king and his son Jonathan replaced with the hope inspired by the forthcoming reign of a new king, David. It is worth noting at this point that this new Jacobs recording includes a penetrating essay on the oratorio by Pierre Degott, which, like that of Ruth Smith in the Archiv set, is particularly illuminating on the political and social background of the work.

Saul is generally recognized

as being one of Handel's most powerful dramas, a blazing work, whose

overwhelming choruses, and rich diversity of orchestral weight and sonority

proclaim throughout the white heat of inspiration. Not surprisingly for a

conductor whose reputation stands as a supreme interpreter of 17th- and

18th-century music drama, it is this side of Saul that René Jacobs

highlights. Placing his orchestra in the forefront of the soundstage, Jacobs

draws from Concerto Köln playing of a fire and, at times, trenchancy that

emphasizes the huge impact of Handel's innovative orchestral writing. It's

an approach that both pays dividends, and can have its downside. Key

moments, as when Saul's jealousy of David boils over, have a spine tingling

frisson that is unequalled in other performances. The major downside is that

Jacobs's vision of the oratorio can at times lead him dangerously close to

confusing drama with melodrama. The great Witch of Endor scene is perhaps

the prime example. Not only is the decision to encourage Michael Slattery's

Witch to camp-up his utterances misconceived, but Jacobs allows all manner

of extraneous continuo effects, exaggerated dynamics, and anachronistic sul

ponticello effects not asked for by Handel in what is already one of his

most radically scored scenes. And while on the subject of solecisms, one

wonders why Jacobs found it necessary to reduce the mimetic impact of the

TTB chorus, “Along the monster atheist strode,“ (No. 2) by allotting it to

solo voices Regrettably, this is far from the end of Jacobs's tamperings

with the score, which are most damaging in his refusal to allow Handel's

carefully considered organ contribution to make its full impact. In many

places this fundamentally alters the depth and breadth of sound the composer

envisaged, and in the second allegro section of the Overture, Jacobs goes so

far as to replace his rather weedy chamber organ with an oboe in the solo

passages. In this respect alone, McCreesh has a significant advantage, his

use of a fine contemporary English organ given its due prominence imparting

to the many passages in which it supports the choruses a weight absent in

the new recording. Not surprisingly for a work as demanding as Saul, all three main contenders have weaknesses in the casting of major solo roles. The Jacobs is a critical one, because it involves Saul himself. Gidon Saks seems to have been chosen for his vocal acting, which in any event is often blustering-ly unsubtle, rather than the quality of his grainy and cavernous bass. Although Saks makes a good attempt to convey Saul's conflicting emotions in the Witch of Endor scene, he is overall no match for either Gardiner's black-voiced Alastair Miles, or McCreesh's lighter-toned Neal Davies, whose Saul I find increasingly insightful. The role of David was originally written for a mezzo, but is almost always allotted today to a countertenor. I've much admired Lawrence Zazzo's work in the past, and here, apart from the odd moment of difficulty and a tendency to use too much vibrato (the opening word of his first aria “O King, your favors“ gets him off to an inauspicious start), he sings with style and sensitivity. Much to be preferred to Gardiner's Derek Lee Ragin, Zazzo can count himself unfortunate to also come up against Andreas Scholl, who gives McCreesh one of the finest performances of his distinguished career.

All three sets feature an

excellent Jonathan, Jeremy Ovenden here singing with manly virility; he is

especially sensitive in the tense exchanges with his father. Rosemary Joshua

is exquisite as Saul's gentle daughter Michal, revealing from the outset of

“He comes, he comes!“ (No. 6) the delight and charm of a young woman

headlong in love. Her assumption of the role eclipses that of Nancy Argenta,

the major disappointment of the McCreesh set, without effacing memories of

Lynne Dawson's lovely singing for Gardiner. But I was disappointed with Emma

Bell, of whom I had heard much (she has recently made a Handel aria CD).

Although obviously a highly talented singer, she does not persuade me that

she is a natural Handelian, or that she has caught the proud haughtiness of

the elder sister Merab anything like as effectively as did Susan Gritton on

Archiv. All the smaller roles are well filled for Jacobs, with Slattery a

fine High Priest (given all three of his often-cut numbers in act I), and

bass Henry Waddington making a vivid impression with his superbly projected

Samuel, a small but critical role. Here surely is a potentially outstanding

Saul of the future. The RIAS choir responds to Jacobs with excellent

ensemble and considerable fervor, without always being able to project the

unfamiliar English words with the clarity and incisive articulation obtained

by both Gardiner and McCreesh. While there can be little doubt as to Jacobs's commitment to Handel's first great oratorio, he ultimately fails to convince me that he has lived with Saul long enough to penetrate all its depths. It is a performance dominated by raw, red-blooded emotion, but also deeply considered in the mourning scenes that follow the deaths of Saul and Jonathan. For many, that will doubtless be enough, particularly as HM has managed to include the whole work (with the exception of cutting the final part of the Overture) on two discs rather than McCreesh's three. Yet, for those who would know deeper truths about Saul, it is the Archiv set that will continue to hold pride of place. It is indeed one of the glories of the Handel discography.

| |

|

Sélectionnez votre

pays et votre devise en accédant au site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|