Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: David

Johnson

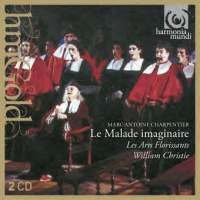

N.B. :The initial version issued by Harmonia

Mundi in 1990 was only 78:56 minutes long. The HM Gold version released in

2012 brings us in its entirety the original production. It now runs for

1h30. The French branch of Harmonia Mundi now makes full amends in a captivating reading of the music that Marc-Antoine Charpentier contributed to Molière's last play, Le Malade imaginaire. Molière died of a brain hemorrhage while acting the role of the hypochondriac Argan during the initial run of this play in 1673, and that put an end to his collaboration with young Charpentier. A brilliant instinct for talent had led Molière to choose Charpentier as Lully's replacement when Lully decided he wanted a larger share of the pie and began to write full-blown operas under the patronage of Louis XIV. Charpentier, recently returned from studying with Carissimi in Italy and as yet unknown save for some church works, was not the obvious second choice he would seem to us to be, but Molière (musical himself and the son of a musician mother) spotted Charpentier's genius, tried him out in some patchwork for revivals of La Comtesse d' Escarbgnas and Le Manage forcé in 1672, and then collaborated with him fully in Le Malade imaginaire, which was to prove the last of his comedy-ballets (he preferred to call them comédies meslées de musique et de danses— comedies mixed with music and dances). Molière's sudden death was a double tragedy—the loss to France of its greatest comic genius and of one of its potentially greatest opera composers. Charpentier went on to live a long life, but Lully (rhymes with bully) saw to it that he never got another chance on the professional stage of Paris until Lully himself died and his royal patent of exclusivity lapsed. Only then was Charpentier able to compose his one and only full-dress opera, Médée. Lully's jealousy extended over to Charpentier's one collaboration with Molière: he persuaded the king to restrict the number of singers and instrumentalists that could be used in dramatic productions except at the Opéra, where he held exclusive rights, making it necessary for Charpentier to revise and miniaturize his score for Le Malade imaginaire for several subsequent revivals. On the title page of the last of these revivals, in 1685, Charpentier wrote, with obvious exasperation, “Le Malade imaginaire rajusté autrement pour la troisième fois“—“Le Malade imaginaire readjusted in another way for the third time.“ The version that William Christie and his Arts Florissants performed in April 1990 at the Châtelet Theatre in Paris and then took into the studio to record, is the complete 1673 version of Charpentier's music, with portions of Molière's play as needed in order to make sense of the music. In a footnote at the end of the libretto, Harmonia Mundi informs us that in order to contain the work on a single compact disc it was necessary to cut some of the repeats in the ballet music and to omit the “Dernière et Grande Entrée de Ballet“ completely. These cuts, amounting to about eight minutes of music, were not made in the cassette format (HMC 401336; total timing 87:16), which will be preferred by those who want every last note of Charpentier's score. It is a very substantial score and would make for a very long evening in the theater if given with the uncut Molière comedy. Charpentier provided an elaborate prolog celebrating, in the usual sycophantic style of the age, the heroic achievements of Louis XIV and designed for a court performance that never took place; a “pseudo-operatic scene“ (to quote the note-writer, H. Wiley Hitchcock) for act II; intermèdes (interludes) after acts I and II; and the closing Cérémonie des Médecins which mixes spoken and choral passages in hilarious fashion, all done in pidgin-Latin. What impressed me about Charpentier's long-neglected score is the variety of its styles, both old and new. The overture offers some splendid trumpets-and-drums proclamations in the manner of the Venetian Gabrielis, and the succeeding tribute to the Sun King is in the style of a Grand Motet, with solos echoed by choruses, but also includes more dance-like episodes and a wonderful use of echo effects on the name “Louis.“ The Première intermède is sung in Italian and French. The amorous opening lament for tenor is in the style of Monteverdi, a bit out of date for 1673. The following querulous and amusing attack by an Old Lady on all amorous fops might have come from one of the comic scenes in a Cavalli opera. Dominique Visse, that wonderful male alto (calling him a countertenor is an injustice), throws all moderation to the wind in imitating the voice and sentiments of a sour old woman. The closing episode of this first interlude takes us back still farther than the styles of Monteverdi and Cavalli, to that of the madrigal operas of Banchieri and Vecchi, as the miser Punchinello (spoken with brilliant comic effect by Alain Trétout) has his nose twisted thirteen times and his back cudgeled half a dozen more before he gives up the six coins demanded of him by a chorus of drunken archers. Christie and his performers ring the utmost in roustabout, violent humor from this scene. The next scene is designated in the plays as a “Petit Opéra Impromptu,“ and Argan, the imaginary invalid of the title, takes part (as actor, not singer) along with the young hero and heroine of the play, Cleante and Angélique. They practice a little love duet, ostensibly to amuse Argan's guests, but he grows angry at their evident devotion to one another (he is planning to marry his daughter Angélique to a fatuous, would-be doctor) and puts an end to this operatic impromptu. The actor who created the role of Cleante was not much of a singer, but the part of Angélique was given to a singing actress; Charpentier takes account of their strengths and limitations in this scene and Christie cannily casts the two roles accordingly. The Deuxième intermède is a “Turkish“ entertainment, prescribed for the imaginary invalid by Doctor Purgative because of its pleasing and salubrious quality. Charpentier takes advantage of the opportunity to write a series of solos and a concluding ensemble of melting (and very Italianate) loveliness. For the famous finale, the Ceremony of the Doctors, Charpentier composed a second overture and an Air des Tapissiers, both in his most appealing manner. Molière's clever, rhymed macaronic Latin is not translated in the accompanying booklet, unlike the rest of the text, which is provided with an excellent English translation. The omission was undoubtedly deliberate, apparently on the premise that you either have the culture to catch on to this universal language or you are unworthy to know what is taking place. The Praeses who starts things off in rapid, French-inflected Latin is none other than William Christie himself. Since there is orchestral comment after each of his strophes, he must double at the same time as conductor. He does himself proud in both capacities. After him, each of three doctors (spoken by singers) question the imaginary invalid—who has decided to become a doctor himself—on the medical treatment of a variety of illnesses. They get the same reply for every malady: “Clysterium donare,/Postea seignare,/Ensuitta purgare“ (basically, bleed and purge). This all-purpose answer satisfies the learned doctors of the medical college, who welcome Argan into their ranks with repeated choruses in vigorous madrigal style (“Bene, bene, bene respondere:/Digus, dignus est entrare/In nostro docto corpore“).

With Christie pulling out all

his instrumental stops, including tuned bells, the scene plays marvelously

well. So does the entire recording. Along with those of Marc Minkowski, it

sets new standards of brilliance and daring for the authentic-performance

era. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|