Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Reviewer: Brian

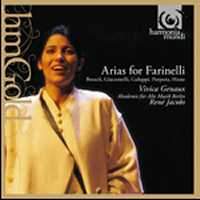

Robins This is a disc that throws down the gauntlet in no uncertain terms, whipping up the current controversy over the type of voice that should be used today to essay the great castrato roles of 18th-century opera. It is a rather delightful paradox that one of those who has swung firmly behind the belief that women are better suited to these roles should be René Jacobs, who in a former life sang many such roles as a male alto. Jacobs, along with Alan Curtis (see p. 32 of Fanfare 25:2), is now firmly of the opinion that the music expressly written for such god-like singers as Farinelli (Carlo Broschi) and Senesino are unsuited to the male falsetto voice. The views of such noted conductors of Baroque opera as Curtis and Jacobs would command respect at any level, but they are also based on strong contemporary evidence. In a long, closely-argued essay provided with the present disc, Jacobs concludes that the falsetto voice cannot command the powerful chest notes singers like Farinelli and Senesino were known to possess (Curtis makes the same point). Progressing further, we come to a truly sobering thought for all present-day singers approaching this repertoire. Quoting Johann Adam Hiller, a singing teacher successor of Bach’s in Leipzig, Jacobs notes that low notes were supposed to be sung with a full, rounded tone, and that the further the singer progressed toward the upper register, so the singing should become ever more softer in order to avoid forcing the voice. Oh . . . er . . . where does that leave the explosive fortes on top notes I’ve complained of so often in Fanfare and elsewhere that I have almost reached the point of giving up commenting on them? All this, of course, leaves the poor young American mezzo Vivica Genaux with not only the formidable task of attempting to measure up to one of the greatest singers of all time, but of also employing a technique that will stand comparison with the paradigmatic standards of the day to which Jacobs has drawn our attention. Happily, Genaux (who both Bernard Jacobson and I praised for her singing of the title role in Curtis’s outstanding recording of Handel’s Arminio (25:2)) emerges from the test with flying colors. For a start, the voice itself really is a special instrument, liquidly lustrous in cantabile writing, capable of highly impressive agility in quicker music, and evenly produced throughout its wide range. I suppose if one applies the “Hiller test,” it would have to be admitted that some notes in the upper range are still too loud, but compared with most of her contemporaries Genaux is pretty exemplary in that respect. To hear her formidable technique at its most stunningly virtuosic, turn to Qual guerriero by Farinelli’s brother Riccardo Broschi (c. 1698–1756). This is a “simile” aria comparing the strength and courage of the warrior with that of a love-stricken heart. It calls for a strong chest register (listen to the words “in campo armato”), a huge range encompassing wide leaps, and fast runs and divisions, all of which demands are triumphantly met by Genaux with no hint of ugly aspirates in the acutely articulated divisions. Equally impressive in a different way is Genaux’s singing of Quell’ usignolo, one of those long (over 14 minutes), vapid “nightingale” arias so beloved of the 18th century. Composed for Farinelli’s role of Epitide in the little known Geminiano Giacomelli’s Merope (Venice, Carnival 1734), it finds Genaux skillfully avoiding the vulgarity generic to such arias by dint of control, evenly-produced vocal production, and tasteful command of ornamentation (prepared by Jacobs, and another topic on which the conductor has some outspoken comments to make). Listen, for example, to her exquisitely weighted scales in the cadenza. That arias sung by virtuoso castratos were not all showy display can be heard in Hasse’s Per questo dolce amplesso, the best aria on the disc, and already a great favorite before Farinelli sang it in a London version of Artaserse in 1734. It displays the composer’s well-known gift for gentle, melodically inspired cantabile, a quality that allows Genaux to express the bitter-sweetness of parting to infinitely touching effect in a performance that demonstrates that remarkable evenness of tone in slower motion. It would be tedious to mention every aria, all of which have been cleverly selected to show some feature of the range of music undertaken by Farinelli. Each has its own special pleasures, both as music and in Genaux’s performances; my only other reservation concerning which is an occasional excess of vibrato on sustained notes (the word “tanto” in Broschi’s melancholy Ombra fedele is a specific instance). Otherwise, there can be nothing but praise for a singer who already possesses an extraordinarily stylish command of this difficult bel canto repertoire. The support of Jacobs and the Berlin Akademie is exceptionally alert and positive, with the orchestra giving a fine account of the appealing Galuppi string concerto that sensibly provides a midway break in the program. The presentation is lavish, including as it does not only Jacobs’s essay, but also one on Farinelli by scholar Reinhard Strohm, and a color reproduction of a portrait of the handsome castrato in all his deified glory. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|

.jpg)