Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: George

Chien

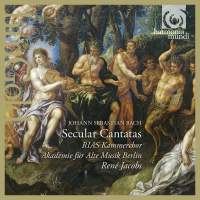

As most serious collectors know, the only musical enterprise that Johann Sebastian Bach did not master—because he never tried it—was opera. It was postulated by the Romantic mythmakers that this quintessential church composer had no interest in the vulgar world of opera. More likely what Bach lacked was not the interest, but the chance. And it seems fairly evident that he knew how. He was obviously capable of building dramatic tension in his music; he was no stranger to characterization; and, when called upon to do so, he could tickle a funny bone. Furthermore, Bach kept abreast of the trends and used whatever he felt was appropriate in his own compositions, sacred as well as secular. Indeed, the Leipzig cantor's musical outlook may have been much less conservative than has been commonly portrayed. Robert L. Marshall suggests that the reason for Bach's creative silence six years after assuming the Leipzig post was a profound dissatisfaction with the city's conservative, provincial musical outlook. Had his quest for a position in cosmopolitan Dresden found success, can we doubt that Bach would have tried his hand in the theater? Bach came closest to writing an opera in a handful of secular cantatas with plotted librettos and assigned roles for the vocal soloists. But these were more sketches rather than full-fledged operas. None runs much longer than half an hour, and none has a very complicated plot—a simple conflict and its ultimate (and successful) resolution. Jacobs has recorded three of these miniature music dramas. One (BWV 201) pits traditional, learned music against the newer simpler idiom (style galant) with Bach's Beckmesser, presumably, besting his Walther. In the second (BWV 205) a crotchety god, bent on havoc, is dissuaded by hearing the name of the cantata's honorée. The third (BWV 213) depicts the prototypical jock, forced to choose between a life of virtue or one of vice. I'm confident that Bach's audiences were not surprised by his decision, though avid readers of today's tabloids and sports pages might reasonably question its credibility). Since all were written for festivities of one sort or another, they tend to be upbeat and simplistic, leading Malcolm Boyd to doubt whether greatness in the opera house could derive from such frail beginnings. (Had I been a betting man living at the time, I suspect that I'd have put my money on the man who composed the St. Matthew Passion.) Incidentally, if Hercules sounds familiar, it may because Bach used much of it a year later for his Christmas Oratorio. Jacobs's performances are about as fine as one could hope for in these cantatas, with spirited singing, good humor, and excellent contributions by the instrumental ensemble. Harmonia Mundi has also done its part, with first-rate sonics. Text and translations are provided. By the way, the cover illustration, from a painting by Hendrick de Clerk, shows Apollo playing a viola and Marsyas with panpipes. Phoebus's instrument was the lute, but, hey, this happens when you don't commission original artwork. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|