|

|||||||

|

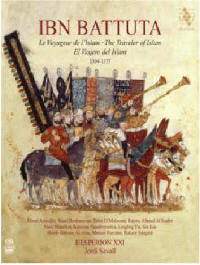

Une évocation historique, géographique, littéraire et musicale de la rihla d’Ibn Battuta La découverte des Voyages d’Ibn Battuta dans la belle édition, traduite au catalan par l’historienne Margarida Castells et le poète et arabiste Manuel Forcano, publiée par les éditions Proa (Barcelone, 2005), fut la source inspiratrice qui a été à l’origine de la réalisation de ce nouveau Livre/CD. L’invitation au voyage comme moyen d’apprentissage et source de connaissances a été, selon les plus anciennes traditions prophétiques, préconisée par le prophète Mahomet lui-même ; il poussait ses croyants à voyager n’importe où, à la recherche du savoir et de la connaissance. Une des citations qu’on lui attribue nous dit : « Cherchez la connaissance jusqu’aux confins de la Chine ». La lecture du fascinant récit de voyage d’Ibn Battuta, nous permet de constater et découvrir ce genre littéraire à part entière ; la « Rihla qui désigne le voyage et, par la suite, le récit que l’on en fait. ». Ce genre avait déjà été initié par Ibn Jubayr (1145-1217), le premier grand voyageur arabe originaire de Xativa (Valencia). Ibn Battuta était avant tout un véritable voyageur, et ses observations ne sont pas scientifiques mais plutôt personnelles. Malgré cela, elles apportent d’importantes connaissances sociologiques, coutumières ou historiques aux chercheurs. Citons un exemple curieux au sujet des femmes des Maldives, musulmanes et très pieuses, mais qui ne s’habillaient que jusqu’à la taille et ne couvraient pas le haut de leur corps, ni leurs cheveux : en qualité de qadi et de Maghrébin, Ibn Battuta a violemment condamné et tenté d’interdire cette pratique qui le choquait, sans succès toutefois. Le souverain de l’île à cette époque était une femme, et le régime du droit matriarcal était appliqué. Comme le remarque si bien Oriane Huchon dans son intéressant article « Ibn Battûta : vie et voyages », celui-ci a rédigé ses Voyages à destination d’un public musulman averti du contexte politico-religieux du dâr-al-islam au XIVe siècle. Il n’a pas nécessairement explicité des éléments qui devaient lui sembler triviaux mais qui auraient apporté beaucoup de clés de compréhension au lecteur occidental. C’est en partie pour cette raison qu’il est demeuré longtemps inconnu des Européens. Jusqu’au XIXe siècle, sa chronique est connue principalement dans le monde musulman. Ce n’est que lorsque la chronique de ses Voyages a été traduite dans le monde occidental, qu’elle a été connue à partir de la deuxième moitié du XIXe siècle, surtout grâce aux traductions en allemand, puis en anglais et en français, publiées intégralement en 1858 par C. Defrémery et B. R. Sanguinetti et rééditées en 1997. C’est le sultan du Maroc qui commissionne en 1356 un jeune érudit d’origine andalouse, Ibn Juzzay, pour transcrire toutes les aventures d’Ibn Battuta. Son récit de voyages est écrit à la première personne et nous donne tous les renseignements qui nous sont parvenus à propos du Marocain. On apprend ainsi qu’il a épousé et répudié un nombre important de femmes après en avoir pris un nombre encore plus important comme concubines. On sait aussi qu’il a mené une vie de courtisan, subsistant avec les grâces que lui apportaient les puissants des pays qu’il visitait. On comprend surtout l’importance de la religion dans son périple, car Ibn Battuta était avant tout un voyageur musulman. La plupart des informations dont nous disposons à son propos proviennent de ses écrits personnels. Dans son ouvrage co-rédigé en 1356 avec Ibn Juzzay, il relate ses aventures et ses multiples voyages qui l’ont conduit aux quatre coins du monde connu de 1325 à 1354. On apprend ainsi qu’Abu Abdallah Ibn Battuta est né à Tanger en 1304, sous la dynastie Marinide. Il fait des études de droit coranique et quitte Tanger dans le but d’effectuer le pèlerinage à La Mecque, ou hajj, en 1325. Il atteint l’Arabie en un an et demi, visitant au passage l’Afrique du Nord, l’Égypte, la Palestine et la Syrie. Son pèlerinage effectué en 1326, il découvre la Perse et l’Irak, puis retourne à La Mecque. Il embarque ensuite à destination de l’Afrique de l’Ouest, et navigue jusqu’à Kilwa, en actuelle Tanzanie, après être passé à Mogadiscio, Mombasa et Zanzibar. Au retour, il visite Oman et le Golfe persique avant de se rendre de nouveau à La Mecque. Vers l’an 1330, il reprend la route. Il décide d’aller en Inde dans le but d’être engagé par le sultan de Delhi. Pour ce faire, il voyage pendant trois ans. Il passe par l’Égypte, la Syrie, Constantinople, l’Asie Mineure, la Mer Noire et l’Afghanistan. Ibn Battuta demeure huit ans en Inde, employé par Muhammad Tughluq, le sultan de Delhi. Il se voit confier un poste de qadi, de juge. En 1341, le souverain le commissionne pour mener à bien une expédition vers la cour de l’empereur mongol de Chine. Le navire s’étant échoué au sud-ouest de l’Inde, Ibn Battuta en profite pour voyager pendant deux ans aux Maldives, en Inde du Sud et à Ceylan (actuel Sri Lanka). Aux Maldives, il exerce aussi une fonction de qadi. En 1345, il se rend de lui-même en Inde par la mer. Il en profite pour visiter le Bengale, la Birmanie, l’Île de Sumatra et le sud-est de la Chine jusqu’à Canton. Il affirme avoir voyagé jusqu’à Pékin par voie terrestre, mais cette affirmation semble douteuse. En 1346-1347, Ibn Battuta retourne à La Mecque et y effectue une dernière fois le hajj. En 1349 il rentre au Maroc, puis visite Grenade. Finalement en 1353, il accomplit son dernier voyage, qui le mène à travers le Sahara jusqu’au Mali et au Soudan. En 1355, il s’établit au Maroc pour ne plus repartir. Avec ce Livre/CD nous avons voulu évoquer le merveilleux voyage d’Ibn Battuta avec une sélection de textes, réalisée par Manuel Forcano et Sergi Grau, qui illustre les principales étapes de son itinéraire, accompagnées des musiques correspondant aux différentes cultures de chaque pays ou de la région visitée. Pour les moments historiques se référant à des événements qui ont eu lieu en Occident, nous avons utilisé des musiques de l’époque correspondant au pays ou lieu mentionné : la mort de Marco Polo (1324), le voyage dans un bateau catalan (1346), la conquête de la Sardaigne et la présence de Pierre IV sur l’île (1353), la Bataille de Baeza (1368) ou son passage dans des territoires chrétiens d’Orient, ou encore son arrivée à Constantinople (1334). Tandis que pour la majorité des moments du récit qui ont lieu dans des pays d’Afrique, dans la Grenade de l’Al-Andalus, ou dans le Proche ou le Lointain Orient, nous avons majoritairement choisi des chansons et des danses provenant des traditions de chaque lieu. Dans la plupart des cultures orientales, les musiques et les chants pratiqués aujourd’hui, sont souvent le résultat d’un long processus de transmission et d’improvisation. Ces musiques sont restées vivantes jusqu’à nos jours, du fait d’avoir été transmises par des traditions orales très anciennes (et souvent impossibles à dater d’une manière précise), dans lesquelles l’art de l’improvisation est toujours un élément essentiel de l’interprétation et de la conservation. C’est justement pour bien saisir toute la richesse et spontanéité de cet art de l’improvisation, la raison principale pour laquelle nous avons choisi d’offrir la musique des deux parties du voyage d’Ibn Battuta, à partir des deux enregistrements « live », réalisés en direct durant les deux différents magnifiques concerts ; le 1er CD contenant la Première Partie du Voyage, correspond au concert donné à Abu Dhabi, dans l’Emirates Palace-Auditorium le 20 Novembre 2014 (ce qui explique que les textes soient récités en Arabe et Anglais), et le 2e CD contenant la Deuxième Partie du Voyage, correspondant au concert donné à Paris, dans la grande Salle de La Cité de la Musique-Philharmonie de Paris, le 4 Novembre 2016 (ici avec les textes récités en Français). Un autre aspect aussi très important dans notre proposition demeure l’utilisation des instruments en fonction du lieu et des traditions historiques. Ce qui veut dire que, – à part les musiques historiques occidentales, pour lesquelles nous utilisons les instruments médiévaux en usage : vielle, rebec, rebab médiéval, cistre, luth médiéval, organetto, chalemie, flûtes, cornemuses, et percussions diverses –, toutes les musiques de tradition orientale sont interprétées par les instruments spécifiquement joués dans les différentes cultures des pays visités par Ibn Battuta : oud marocain et ney, pour les pièces arabes, oud turc, qanun et kaval pour les musiques turques, le santur pour l’Irak et la Perse, le rebab et le zir baghali pour les pièces d’Afghanistan, le sarod et la tabla pour les musiques de l’Inde et des Îles Maldives, le pipa et le zheng pour les pièces Chinoises, et la kora et la valiha pour évoquer l’Empire du Mali. La réalisation de cette grande fresque à la fois littéraire, historique, géographique et musicale, a été possible grâce à la riche diversité des textes et des musiques choisies, et aussi grâce à la merveilleuse capacité créative et interprétative d’une équipe de chanteurs et de musiciens exceptionnels, provenant d’Hespèrion XXI pour les musiques occidentales, et des pays mêmes où Ibn Battuta a séjourné pour les musiques orientales : Maroc, Syrie, Bulgarie, Grèce et Turquie (une partie des pays correspondant à Byzance et l’empire Ottoman), et également le Proche Orient, la côte orientale d’Afrique et d’Arabie et Mali, Madagascar, Perse, Afghanistan, Arménie, Inde et Chine. Finalement c’est grâce à la beauté et l’émotion que portent toutes ces fascinantes musiques, que nous pourrons voyager de nouveau avec Ibn Battuta, et lui rendre hommage pour son extraordinaire « Rihla ». C’est aussi grâce au pouvoir de la musique, que nous pourrons revivre l’enchantement de quelques-unes des principales étapes, vécues durant ses trente années de pérégrinations et de découvertes : aventures, descriptions et expériences personnelles, racontées avec charme et éloquence par l’un des plus grands voyageurs de tous les temps. JORDI SAVALL

|

|||||||

|

ENGLISH VERSION An historical, geographical, literary and musical evocation of Ibn Battuta's Rihla

The inspiration for this new new CD-Book was our discovery of the Travels of Ibn Battuta, translated into Catalan by the historian Margarda Castells and the poet and Arabist Manuel Forcano in the handsome edition published by Proa (Barcelona, 2005).

According to Islam's earliest prophetic tradition, travel as training and a source of knowledge was advocated by the prophet Mohammed himself; h urged believers to travel far and wide in their search for wisdom and knowledge. One of the quotations attributed to him is "Seek knowledge even unto China." The reader of Ibn Battuta's fascinating travelogue discovers and experiences the full character of this literary genre, the "rihla", which designates both th ejoumey and the narrative of that journey. The genre can be traced back to the writings of Ibn Jubayr (1145-1217), the first great Muslim traveller from al-Andalus (Xativa, Valencia).

Ibn Battuta was first and foremost a traveller, and his observations are personal rather than scientific in nature. They nevertheless provide researchers with important information regarding society, customs and history. One curious example concerns the Muslim women of the Maldives, who, although very pius, dressed only from the waist down, covering neither their hair nor the upper part of their bodies. As a qadi and a Muslim fromn the Maghreb, Ibn Battuta fiercely condemned a practice that he found shocking and attempted to ban it. But it was to no avail. The sovereign of the island at that time was a woman, and the local matriarchal law was applied.

As Oriane Huchon aptly points out in his interesting article "Ibn Battûta: vie et voyages", the author wrote his Travels for a Muslim-readership familiar with the political and religions context of dâr-al-islam, the Muslim world where Islamic law prevailed, in the 14th century. He felt no need to make explicit many things, which to him must have been commonplace, but which would have made the work more accessible to the Western reader. This partly explains why the work remained unknown to Europeans for so long. Until the 19th century, familiarity with his chronicle was mainly confined to the Muslim world. It was not until his Travels were translated in the West that the book became more widely known in the second half of the 19th century, thanks chiefly to the complete translations into German, and subsequently into English and French, published in 1858 by C. Defrémery and B. R. Sanguinetti, and re-edited in 1997.

In 1356 the sultan of Morocco commissioned a young scholar of Andalusi origin, Muhammad Ibn Juzayy, to transecribe all the adventures of Ibn Battuta. Written in the first person, this travel narrative provides ail the existing information we have about its author. We learn that he married and repudiated a considerable number of women after having taken an even larger number of concubines. We also learn that he led the life of a courtier, thanks to the grace and favour of the powerful men of the countries he visited. Above ail, we realise the importance of religion throughout his journeys, for Ibn Battuta was above all a Muslim traveller.

Most of the information we have about him comes from his personal writings. In his book, written in 1356 in conjunction with Ibn Juzayy, he relates his adventures and the many voyages which from 1325 to 1354 took him to the four corners of the then known world.

We learn that Abu Abdallah Ibn Battuta was born in Tangier in 1304, in the time of the Marinid dynasty. After studying Quranic Law, in 1325 he left Tangier to go on hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca. The journey to Arabia took him one-and-a-half years, and on his way lie visited North Africa, Egypt, Palestine and Syria. After completing his pilgrimage in 1326, he toured Persia and Iraq before returning to Mecca. He then sailed for West Africa, travelling as far as Kilwa, in present-day Tanzania, after having visited Mogadishu, Mombasa and Zanzibar. On his way back, he visited Oman and the Persian Gulf before returning to Mecca.

In 1330, he set off once more, this time to seek employment in India. His journey there took thee years, during which he visited Egypt, Syria, Constantinople, Asia Minor, the Black Sea and Afghanistan. Ibn Battuta spent eight years in India, in the service of Muhammad Tughluq, the Sultan of Delhi. He was appointed a qadi, or judge. In 1341, the sovereign commissioned him to head a mission to the court of the Mongol emperor of China. Before boarding his ship, it sank off the southwest coast of India and Ibn Battuta spent two years travelling in the Maldives, Southern India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). In the Maldives he also served as a qadi. In 1345, lie embarked once more for India. He took the opportunity to visit Bengal, Burma, the island of Sumatra and southwest China as far as Guangzhou (Canton). He states that he travelled overland as far as Peking, although there is serious doubt as to the veracity of this claim. In 1346-1347, Ibn Battuta returned to Mecca, where he made his final hajj. In 1349 he retumed to Morocco and then visited Granada. Finally, in 1353, he undertook his last journey, which led him across the Sahara to Mali and the Sudan. In 1355, he returned to Morocco, where he remained until his death.

The aim of this CD-Book is to

evoke the amazing travels of Ibn Battuta through a selection of texts chosen

Manuel Forcano and Sergi Grau to illustrate the principal stages of his

itinerary, accompanied by music corresponding to the various cultures of the

countries or regions that lie visited. For the historical moments of the

events which took place in the West, we have used music from the period

corresponding to the countries or places mentioned in the text: the death of

Marco Polo (1324), the voyage aboard a Catalan ship (1346), the conquest of

Sardinia and Peter IV's presence on the island (1353), the Battle of Baeza

(1368) Ibn Battuta's journey through Christian territories in the East, and

his arrival in Constantinople (1334). For the majority of the events in the

narrative, which took place in Africa, Granada and the Middle and Far East,

we have mainly chosen songs and dances from the traditions of each

individual place. In most Oriental cultures, the music and songs played and

sung today are often the result of a long process of transmission and

improvisation. This music has been kept alive to the present day, thanks to

their having been transmitted by ancient oral traditions (and are often

impossible to date with any degree of precision), in which the art of

improvisation is always an essential feature of performance and

conservation. To convey an idea of all the richness and spontaneity of this

art of improvisation, we have decided to offer the music illustrating the

two parts of Ibn Battuta's travels from two live recordings of two distinct

and magnificent concerts: the first CD, containing Part One of the Voyage,

corresponds to the concert given in Abu Dhabi at the Emirates

Palace-Auditorium on 20th November, 2014 (hence the recitation of the texts

in Arabic and English), and the second CD, containing Part Two of the

Voyage, corresponds to the concert given in Paris at the Salle de La Cité de

la Musique-Philharmonie de Paris on 4th November, 2016 (with the texts

recited in French).

This great literary, historical, geographical and musical fresco bas been made possible thanks to the rich diversity of the texts and music selected, and also thanks to the wonderful creativity and performance skills of a team of exceptional singers and musicians, members of the ensemble Hespèrion XXI in the Western music, and, in the case of the Oriental music, front those very centuries visited by Ibn Battuta: Morocco, Syria, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey (some of which formed part of Byzantium and the Ottoman Empire), as well as the Middle East, the East coast of Africa and Arabia and Mali, Madagascar, Persia, Afghanistan, Armenia, India and China.

Finally it is thanks to the beauty and emotion of all this fascinating music that we are now able to travel with Ibn Battuta and pay tribute to his extraordinary Rihla. Thanks also to the power of music, we are able to relive the enchantment of some of the principal landmarks of his thirty years of travel and discovery: adventures, descriptions and personal experiences recounted with charm and eloquence by one of the greatest travellers of all time.

JORDI

SAVALL

Translated by Jacqueline Minett | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|||||||